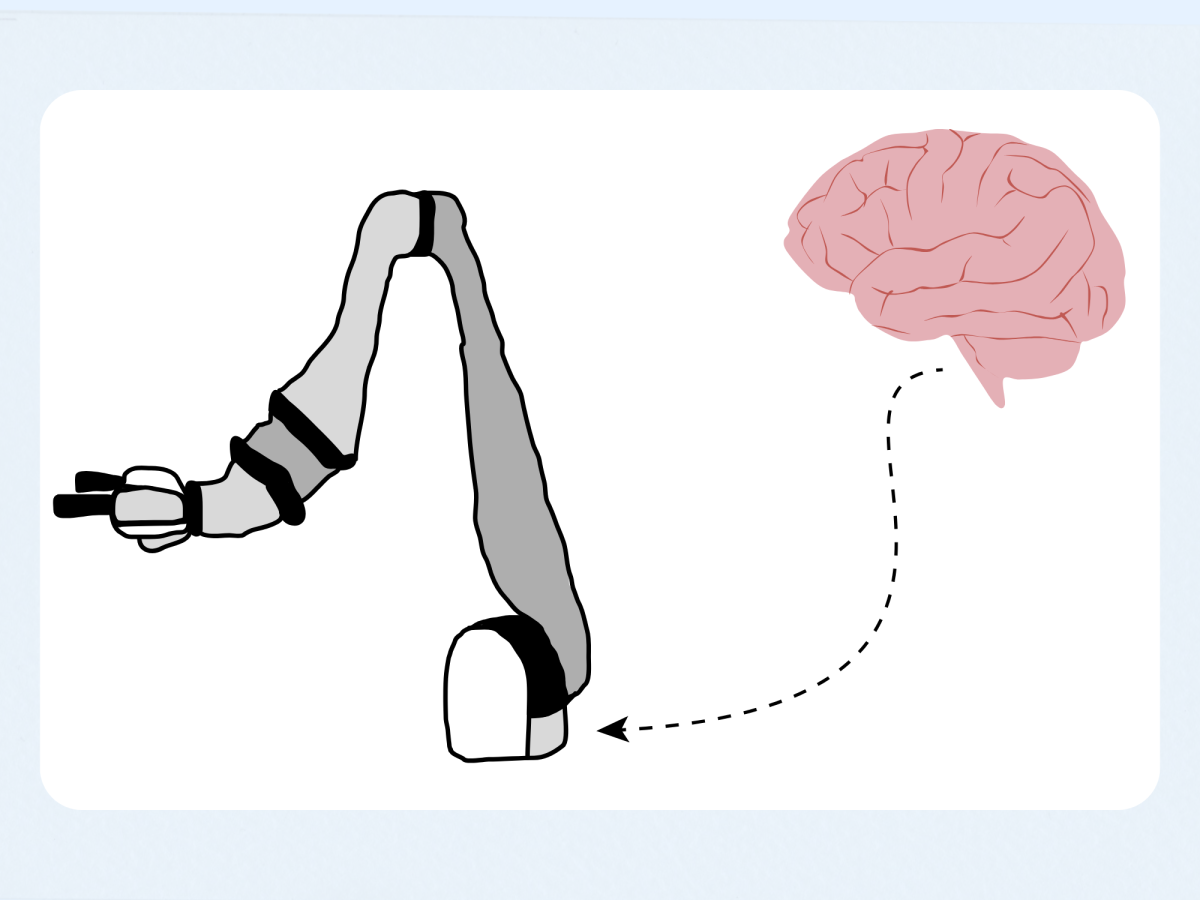

Researchers at the University of California, San Francisco, have created a Brain-Computer Interface—a device that connects the brain to a computer—allowing a paralyzed man to move a robotic arm just by thinking.

Unlike earlier systems that stopped working after a few days, this artificial intelligence-powered BCI stayed functional for seven months without needing recalibration, meaning it did not require frequent manual adjustments to maintain accuracy.

The device relies on tiny sensors implanted on the brain’s surface. These sensors detect neural activity when the participant imagines moving his hand. The signals are then sent to a computer, which translates them into actual movements of a robotic arm. AI helps refine the process by learning how brain activity shifts over time.

Before using the robotic arm, the participant was trained with a virtual one. For two weeks, he imagined moving his fingers while the AI adjusted to his brain patterns. Once he switched to the real robotic arm, he was able to grasp, move, and manipulate objects, including picking up a cup and holding it under a water dispenser.

One of the biggest challenges with previous BCI systems was their inability to maintain accuracy as brain activity naturally shifted each day. The AI in this study solved that problem by detecting and adapting to these subtle changes, allowing the system to remain reliable for months.

The researchers discovered that while the brain’s activity patterns stayed stable, their locations moved slightly over time. This shift made it difficult for older BCIs to maintain accuracy. The AI resolved this problem by continuously learning from the brain and adjusting accordingly.

“This blending of learning between humans and AI is the next phase for these brain-computer interfaces,” Dr. Karunesh Ganguly, a professor of neurology at UCSF, said. “It’s what we need to achieve sophisticated, lifelike function.” This breakthrough has the potential to transform the lives of people with paralysis. Even simple tasks like independently eating, drinking, or opening a door could become possible again.

Scientists are now refining the system to make movements smoother and more natural. They are also testing whether it can function in a home setting, which would be a major step toward real-world use.

Another major breakthrough is that this AI-powered BCI has the potential to be less reliant on research labs. Previous systems needed constant recalibration by scientists, making them impractical for everyday use. This new version remained functional with only occasional adjustments, moving it closer to real-world application. Even after months without practice, the participant was able to regain full control of the robotic arm with just a quick 15-minute recalibration.

There are still challenges to overcome. The participant needed occasional recalibrations, and the system cannot yet restore full movement. Researchers are working to improve the AI so it can better adapt to long-term brain activity changes and require fewer adjustments. In addition, they hope to expand the technology to control other devices, like exoskeletons or computers.

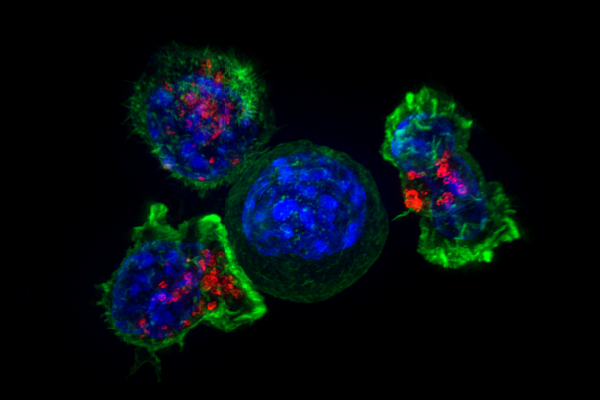

Beyond helping people with paralysis, this research highlights AI’s potential in medicine. If AI can learn directly from the brain, it could assist people with spinal cord injuries, neurodegenerative diseases like ALS, or stroke recovery.

Future brain-controlled prosthetics may not only restore movement but also provide sensation, further improving quality of life. This study marks a significant step toward practical neuro-prosthetic devices.

By combining AI with neural implants, researchers are proving that thought-controlled movement is possible. With further development, BCIs could restore independence to millions of people worldwide and redefine what is possible for those with mobility impairments.