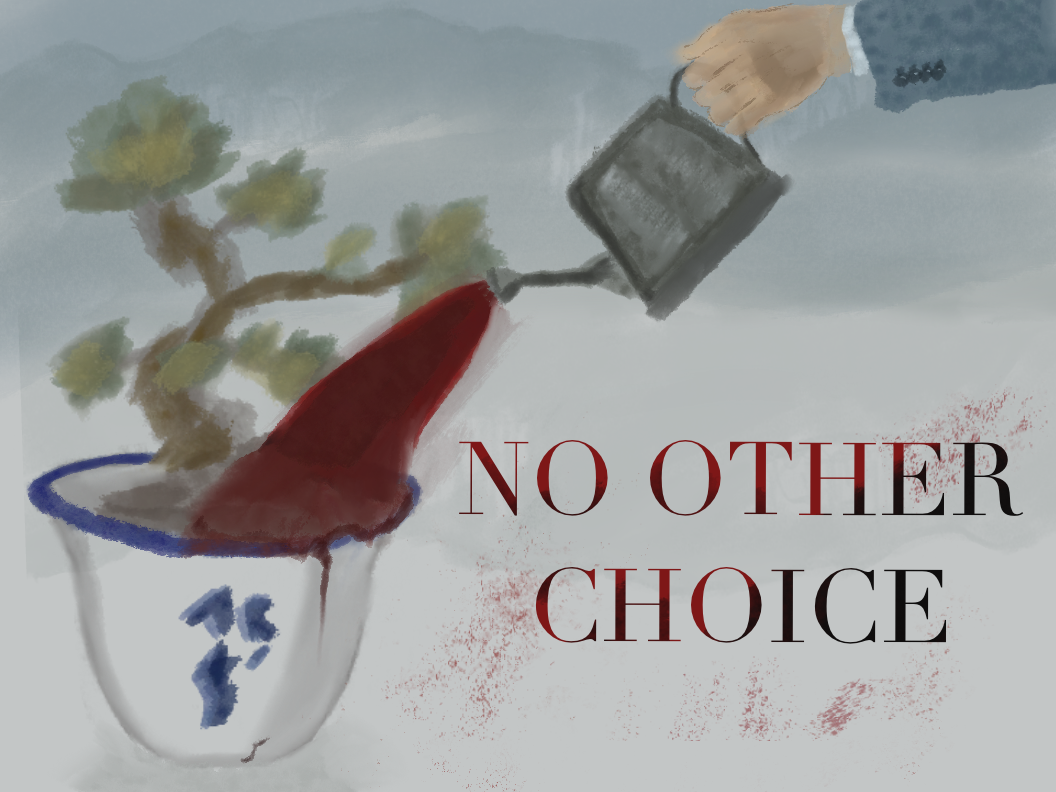

Park Chan-wook’s recent feature film, “No Other Choice,” is a flamboyant, dark comedy about the inescapable link between dignity and employment. Originally based on Donald E. Westlake’s 1997 novel “The Ax,” the film cynically answers what happens when an ordinary worker gets laid off from his job of 25 years.

The film follows Yoo Man-su, an archetype of the successful middle-class family man, and his struggle to retrieve his managerial job at a paper-mill factory when the mill fires him and his coworkers after the company is reacquired. Failing to secure another lucrative position at several other paper companies, Yoo devises a strategic and violent plan to eliminate his competition.

Yoo’s character, brilliantly portrayed by Lee Byung-hun, reveals a much larger issue about job security in capitalism’s zero-sum market.

Like Bong Joon Ho’s “Parasite,” Park’s film is bold in its critique of South Korea’s hyper-capitalism and neoliberalist regime. Yoo’s identity is closely dependent on his career; it takes him weeks to tell his family that he got fired.

Later, we see Yoo attend a support group for those who were laid off, where the men continuously repeat incantations like “I am a good person” and “losing my job is not my choice.”

Ironically, Yoo stays diligent and subservient to the same system that pushed him out of his job. His class struggle transforms into an internal struggle. In an interview with The Hollywood Reporter, Park explained that the solution to our problems can only be found by fighting the system. But very foolishly, the main character begins targeting his fellow colleagues — the poor laborers who are in the same precarious position he is in.

The film’s characters are very intentionally written to heighten the critique against rising automation and technology. Yoo’s youngest daughter is an exceptionally gifted violinist, whose skill can only be cultivated through paid lessons. Indirectly, her artistic flourishing depends on Yoo’s success in eliminating his competition to secure another form of income.

“No Other Choice” is a masterclass in direction. During intense confrontation scenes, Park chose comedic needle drops and boosted the volume of the songs to add absurdity to the scene. Every shot, cut and montage paced the film from one extreme to the other, shifting the tone from thrilling to comedic to tragic.

As seen in the trailer, the camera placement alone showed that it acts as another character in the story. Park zoomed into street mirrors and positions the camera overhead strangers to mimic surveillance. In other scenes, he placed the lens at the bottom of a beer glass to grip the viewer. During the protagonist’s more climactic and confrontational moments, the audience took Yoo’s point of view. The tone drastically shifts based on what Park wants to pay attention to.

The title “No Other Choice” serves as a double entendre that shows up multiple times in the movie. Yoo believes he is left with no other choice in finding work. The excuse the workers and Yoo hear from the new company is that they had no other choice but to lay-off the factory workers in favor of an automatic artificial intelligence-powered system.

The original title written in Korean Hangul has no space in between characters, intentionally placing emphasis on the stress the movie is based around.

It is important to realize Yoo is not a unique individual. The common and expected hard-working character of a worker becomes subversive when the work he does favors only himself. In this story, losing your job is comparable to losing your life.

If Park’s “Oldboy” and “The Handmaiden” are stories of revenge, then “No Other Choice” is a story about a man’s survival. In a world that is continuously capitalizing on automation, competition is at its peak.

Like many of Park’s films, “No Other Choice” is tough to digest, but its handling of grim topics is not only fun and immersive, but also extremely relevant to the current job market. The Oscars have snubbed Park for a deserved nomination as the film becomes another under-appreciated masterpiece.