German researchers reported that one of the earliest indicators of Alzheimer’s disease may be a loss of scent.

The researchers discovered that microglia, the primary immune cells of the brain, inadvertently break down nerve fibers that connect the locus coeruleus in the brainstem to the olfactory bulb in the forebrain.

Simple scent tests could help identify risk years earlier since this breakdown begins before memory issues manifest.

The scientists identified an “eat-me” signal on the outside of the damaged nerve fibers as the underlying cause. Phosphatidylserine, a membrane lipid usually located on the inner face, was translocated to the outside face.

Even if the fibers are generally healthy, microglia interpret that flip as a marker for removal and then prune them. The switch, which transforms a normal cleaning signal into a dangerous one, is caused by abnormal neuronal overactivity early in the illness, according to a press release.

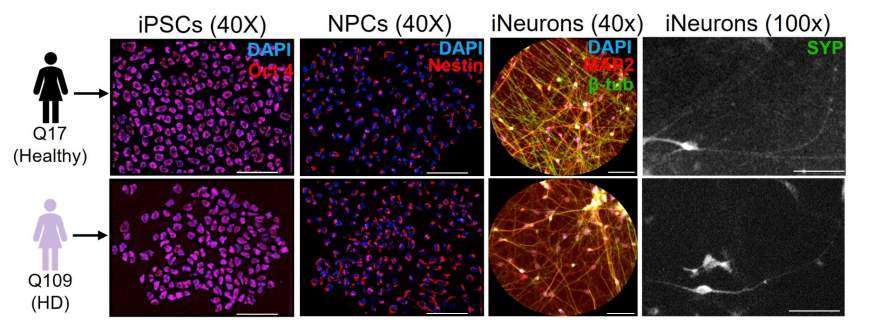

The investigators integrated multiple lines of evidence in the lab. They reviewed positron emission tomography images from patients with Alzheimer’s or moderate cognitive impairment, studied brain tissue from individuals who had the disease and employed mouse models that develop abnormalities like those of Alzheimer’s.

In all these methods, they observed microglial pruning at the locus coeruleus and loss of noradrenergic fibers extending into the olfactory bulb. The combination of imaging, tissue and animal evidence supports the idea that this route malfunctions relatively early in the course of illness.

Clinically, the findings have practical implications for early detection and intervention. If smell tests can identify people beginning to lose these linkages early on, they can receive more comprehensive examinations sooner.

Further, early diagnosis is key because antibody therapies targeting amyloid beta are most effective before significant damage occurs. Therefore, identifying alterations in the olfactory pathway may help guide therapy choices and increase response rates for some individuals.

This work charts a sequence of biological events linking the biology of Alzheimer’s disease to odor loss. To prevent microglia from severing beneficial connections, it also recommends intervention targets including reducing neuronal hyperactivity or preventing erroneous “eat-me” signals.

By transforming these discoveries into screening instruments and treatments, physicians may be able to detect risks earlier and protect the brain circuits essential for both scent and cognition.