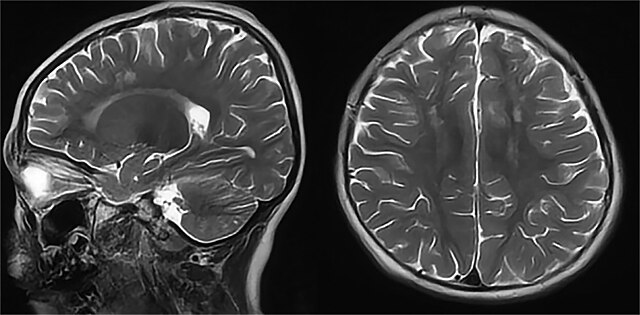

Researchers at Massachusetts General Brigham, Boston Children’s Hospital and Dana Farber Boston Children’s have developed an artificial intelligence tool that may help forecast the return of pediatric brain tumors. By analyzing post-treatment MRI scans, the system can detect subtle changes that may signal a recurrence months before it becomes clinically apparent. This advancement brings the possibility of early, personalized intervention closer to clinical practice.

The focus of this study was gliomas, one of the most common types of pediatric brain tumors. While many cases are treatable with surgery alone, some children face devastating relapses. Doctors can’t easily tell which kids are at high risk, so most patients go through years of frequent MRIs, an experience that’s not only expensive but emotionally exhausting for families.

This issue is where the new AI model steps in. Instead of looking at a single scan, it studies a timeline of brain images taken over several months. By learning how the brain changes after treatment, it can start to spot the subtle signs that a tumor might be returning, even before doctors can see it.

Researchers trained their model on nearly 4,000 MRI scans from 715 pediatric patients across several hospitals, which is a huge dataset for such a disease. The expansive data gave the AI system enough information to learn the complexities of how gliomas recur. The findings showed that the model could predict tumor recurrence within a year of the last scan with an accuracy ranging from 75% to 89%.

This is a major improvement over older models, which usually just looked at single scans and performed only slightly better than chance. The key improvement was the way the scans were aligned over time. By showing the AI how a patient’s brain looked across several months, the system learned to spot small changes that doctors might miss, even ones that appear long before a relapse becomes obvious.

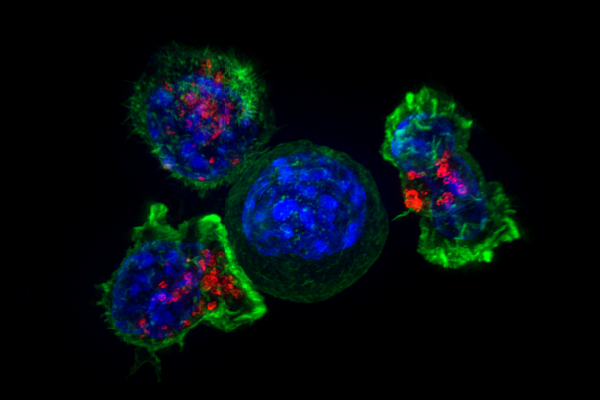

The impact of this technology goes beyond the data. If doctors can spot early signs of relapse in high-risk children, they can step in sooner with closer monitoring or additional treatment. Just as important, if some kids are at lower risk, they may not need as many follow-up scans. This could mean fewer hospital visits, less time under sedation and significantly less stress for families who are trying to return to normal life.

The researchers are approaching their findings with caution. This tool still needs to be tested in real medical settings before doctors can rely on it to guide care. Clinical trials are planned to understand how well these predictions hold up and whether they actually improve patient outcomes. If trials prove successful, it could change the way many conditions, not just brain tumors, are monitored and managed.

What makes this even more exciting is that the researchers have made their model’s code publicly available. Opening the door for others to refine the system, potentially apply it to other types of cancer or even use it for chronic illnesses where changes unfold gradually. It is a glimpse into a future where AI doesn’t just assist doctors, it empowers them to offer more personal, precise care.

This project is a powerful reminder that AI isn’t about replacing human insight. It’s about enhancing it, giving doctors tools to notice what matters, sooner and more reliably than ever before. For the families facing the uncertainty of childhood cancer, that kind of progress means everything.