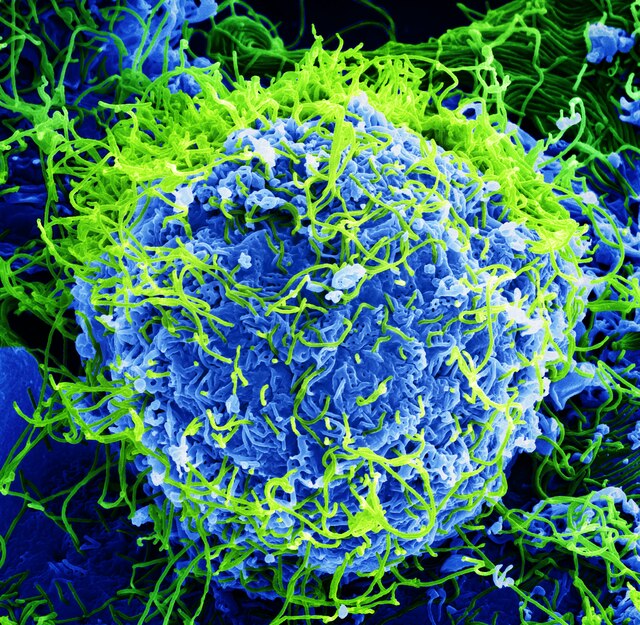

New York City’s subway system, a vital transit network that serves 5.5 million daily commuters, may pose significant health risks due to high levels of iron-rich particles in its air, according to a recent study conducted by New York University. The study identifies train movement, brakes and wheel friction as primary sources of the particulate matter, known as PM2.5, which is fine enough to enter the lungs and the bloodstream.

Researchers found concentrations of PM2.5 averaging 150 to 200 micrograms per cubic meter in subway stations, far exceeding the World Health Organization’s outdoor air quality guideline of 15 micrograms per cubic meter. Some stations, particularly those in Washington Heights, reported concentrations as high as 600 micrograms per cubic meter. For comparison, outdoor PM2.5 levels in New York City range from 15 to 20 micrograms, making subway air pollution substantially worse.

The findings have sparked concerns about the potential health impacts of prolonged exposure to these particles. Lead researcher Dr. Shams Azad explained that while the long-term effects of subway-generated particles remain unclear, research on other types of particulate matter has linked exposure to respiratory and cardiovascular problems. Long-term exposure to PM2.5 contributes to an estimated 2,000 excess deaths from lung and heart disease each year in NYC.

The study highlighted disparities in exposure among different demographic groups. Black and Hispanic commuters face 35% and 23% higher exposure, respectively, compared to white and Asian commuters, due to longer commutes and increased reliance on subways for transportation. Low-income communities also bear a heavier burden, as residents often have less flexibility in choosing their commuting routes and are more likely to depend on heavily polluted stations.

For example, Washington Heights stations, which are some of the deepest in the system, reported the highest pollution levels. Researchers attributed this to poor ventilation and the enclosed nature of these stations. Commuters traveling through Borough Hall in Brooklyn or Fulton Street in Manhattan also encountered significantly elevated PM2.5 levels, though to a lesser extent than stations in Washington Heights.

In response, the MTA dismissed the study’s findings as outdated and methodologically flawed. The research was based on air quality measurements collected between 2021 and 2022, and the MTA argued that it has since implemented enhanced cleaning protocols, including vacuum trains and power-washing platforms, to address particulate buildup.

A spokeswoman for the MTA also criticized the study for comparing short-term subway air measurements to the WHO’s 24-hour exposure standards, arguing that the subway’s pollution sources differ from the fossil fuels that primarily contribute to outdoor air pollution. She emphasized the subway’s role as a “green” transit option, calling it an “engine of equity” for New Yorkers from all communities.

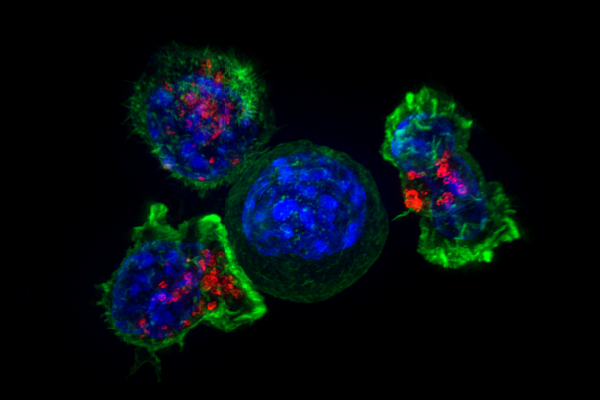

Despite these defenses, the study’s findings raise questions about the health implications of frequent subway use. PM2.5 particles can remain suspended in the air for extended periods, increasing the likelihood of inhalation. Once inhaled, the particles can penetrate the lungs and bloodstream, potentially causing inflammation and exacerbating respiratory conditions such as asthma.

The NYU study, published in the journal PLOS ONE, modeled the exposure levels of 3.1 million commuters across four boroughs using Longitudinal Employer-Household Dynamics data. Researchers combined this with PM2.5 measurements from subway platforms and trains to estimate pollution exposure during daily commutes. The findings indicated a weak but statistically significant correlation between elevated exposure and economically disadvantaged or minority communities.

While the study stops short of providing conclusive evidence about the health risks posed by subway pollution, it highlights the need for further research and potential mitigation efforts. Public health advocates have called for improvements in subway ventilation and additional studies to assess the long-term effects of PM2.5 exposure on commuters.

As the debate continues, the findings underscore a growing tension between the subway’s role as an essential public transit system and its potential health implications for millions of riders.