Remembering Marilyn Stafford: fashion and street photography pioneer

February 6, 2023

Atop a floral chair in 1948, captured candidly on a photo obscured by grain, sat Marilyn Stafford’s first portrait subject: Albert Einstein. While on-set for a documentary about Einstein she was the designated “stills photographer,” marking her abrupt beginning to photography and her signature portrait style. “I’d never used one before, and I went into a panic,” she said in an interview with Digital Camera World when asked how she got the opportunity to photograph Einstein.

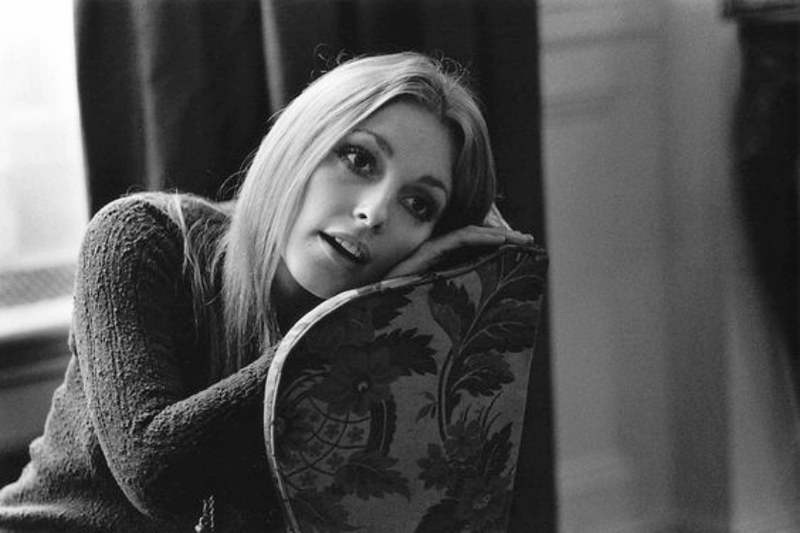

Even as Stafford’s technical skills improved, she retained the same candid, casual quality. This style of photography would stay with her as she captured images of Edith Piaf, Sharon Tate, Eleanor Roosevelt and other iconic mid-20th century figures.

Stafford passed away earlier this month in her home in England at the age of 97. She is remembered for her remarkable photojournalistic and artistic legacy built during a time when women did not commonly occupy those fields. “I like to tell stories,” Stafford said, “and for me, taking a photograph is like telling a story.”

While working in Paris as a freelance photographer throughout the 50s and 60s, she shot most of her subjects on the streets. Some of her photos depicted fabulous, chic models roaming les places de Paris, or “places in Paris,” in kitten heels and calf-length coats. The everyday nonchalance of her alluring subjects heralded fashion’s transition to wearable, practical offerings, making Stafford a pioneer of prêt-à-porter, or “ready-to-wear.” Stafford was hired by haute couture houses for numerous photography assignments. In one memorable photoshoot, she framed the tailored elegance of 60’s Chanel’s prêt–à–porter in a cozy city square, amplifying its intended approachable, everyday setting.

However, in her other Parisian photos, she strayed far from glamor while maintaining her streetset subjects. Some of Stafford’s most notable photos captured homeless men sleeping on streets with tattered blankets, the families of dilapidated homes and children living their youth in alleyways. These photos, which depicted the marginalized members of the city, were a part of Stafford’s photojournalistic work.

Stafford brought her photojournalistic endeavors abroad to capture crises in need of representation. While working as a news photographer in Tunisia, she photographed refugees fleeing areas affected by the Franco-Algerian war. Stafford did this all while6 months pregnant. Seeing the horrible treatment of the people, especially the women, she sympathized, “nobody seemed concerned about the refugee crisis that was unfolding,” she said.

Her powerful images raised international awareness to a refugee crisis that was previously underreported. During another assignment, she photographed the rape victims of the Bangladesh Liberation War, but was unable to capture the razing of their villages, “I was not able to take the photograph I wanted to take,” she said. “The effect of the horror of war and genocide on the people couldn’t be translated onto film. The people there had a look in their eyes I will never forget. It is a photograph I could not get.”

The strength of Marilyn Stafford’s work lies within its duality. She used her skills to elevate luxury fashion photography, a pursuit concerned principally with beauty, while applying her talent to photojournalism, a pursuit which exposes the lack of that same beauty. Regardless of the function her signature style and focus remained the same: capturing subjects candidly.