Upon replacing HIV-infected white blood cells with those of a healthy donor, London researchers found that there is no longer any trace of HIV in the bloodstream of a once infected patient.

The patient, whose identity was not disclosed, has not shown any signs of the disease in 18 months. But doctors are still hesitant to say that a cure has been found. To get more conclusive results, the researchers will have to monitor the patient’s blood for far longer, lead scientist Ravindra Gupta said in Nature, the scientific journal in which the results were first published on March 5.

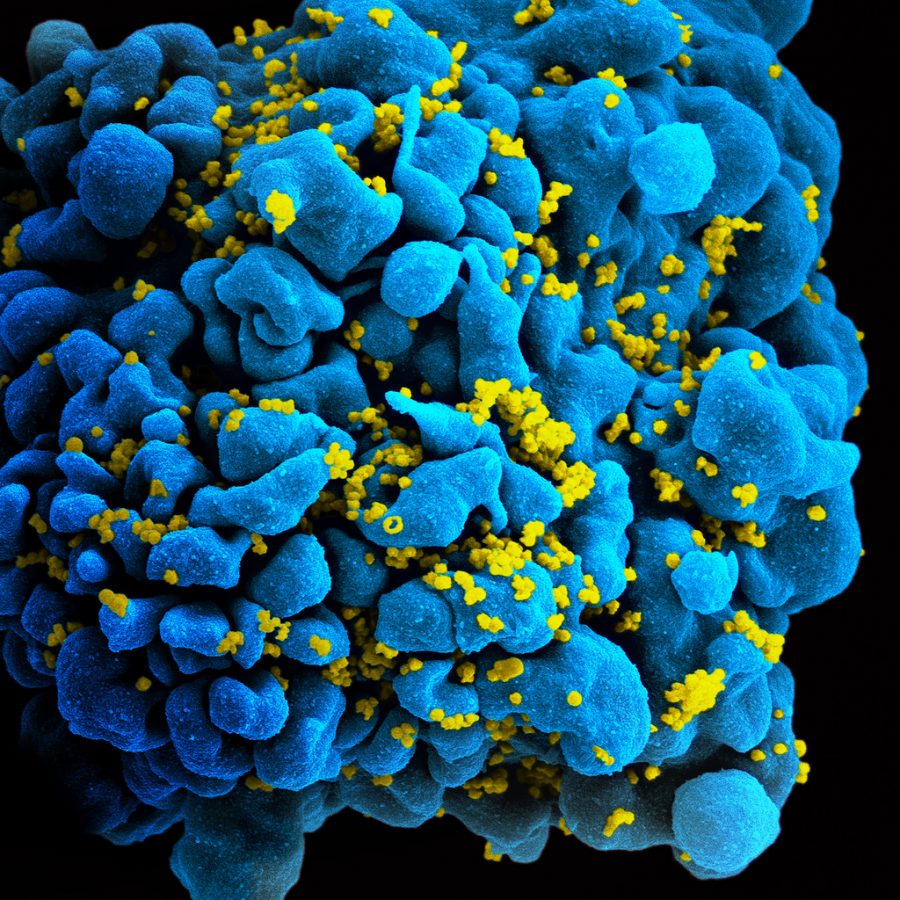

HIV is a sexually transmitted disease that can eventually manifest into AIDS, which destroys the body’s ability to fight against infections. Either condition can be potentially fatal by not allowing the body to respond to infection or disease, making simple ailments and viruses lethal.

The last man who received a similar treatment was Timothy Ray Brown in February 2009. To this day, Brown still doesn’t show any signs of the HIV virus. But the doctors first noticed that this patient stopped showing signs of HIV shortly after his infected white blood cells were replaced with healthy ones.

That patient also stopped exhibiting symptoms of leukemia, which he had in conjunction with HIV prior to beginning the treatment. The researchers’ ostensible triumph in the most recent study demonstrates that the original study conducted a decade ago is not necessarily a one-time success story.

Like Brown, the latest successful patient also had another ailment — a cancer that didn’t seem to be treatable or alleviated by chemotherapy. But Gupta said the latter received a less aggressive treatment than the former to prepare for the infected white blood cell transplant, indicating that it may not be necessary to use aggressive techniques to obtain similar results.

“The new patient was given a regimen consisting of chemotherapy alongside a drug that targets cancerous cells, while Brown received radiotherapy across his entire body in addition to a chemotherapy drug,” Nature reported.

The researchers, who conducted the study at the University of Cambridge in the United Kingdom, “picked a donor who had two copies of a mutation in the CCR5 gene, which gives people resistance to HIV infection.”

“This gene codes for a receptor which sits on the surface of white blood cells involved in the body’s immune response. Normally, the HIV binds to these receptors and attacks the cells, but a deletion in the CCR5 gene stops the receptors from functioning properly.”

But a researcher at Imperial College London pointed out that this treatment may not be suitable for most people with HIV. The treatments were done successfully on two people, both with HIV and cancer that was not responsive to a common chemotherapy treatment. Patients with HIV tend to respond well to antiretroviral drugs, which is the standard treatment for HIV.

There are more than 1 million people in the United States with HIV, according to an info page on the disease from Planned Parenthood.

These results do not indicate that the researchers found a cure for the disease, but they do create more room for research opportunities and expand on the knowledge we already have about combating HIV.

As of March 6, 2018, a third patient from the Netherlands — the “Düsseldorf patient” — was considered functionally cured of HIV after undergoing a similar bone marrow procedure.

It is still impossible to know for sure if the virus is only in undetectable state for now.

If the two other patients respond similarly once they stop taking antiviral medication, the growing number of cases might make it easier to say with confidence that the cure for HIV has been found.

Additional reporting by Ali Hussain.