Ranked-choice voting will disenfranchise voters after tumultuous year and a half

June 25, 2021

Just like the rest of New York City this past year and a half, city voting got turned upside down, but not by the coronavirus pandemic.

This year was the first time that the city implemented ranked-choice voting — a new voting system that allows people to vote for up to five candidates for a single race rather than being able to vote for only one person.

The system is complicated, and in a year when there is just so much else going on to focus on, ranked-choice voting is just another thing that stresses New Yorkers out as the city tries to recover from the pandemic and the economic crisis.

Ranked-choice voting, which will only be used for municipal primary elections, like for mayor and comptroller, was voted into place back in 2019 as a ballot measure, meaning a policy that was listed on voters’ ballots so people could vote on the issue directly. It was passed with 73.5% of the vote.

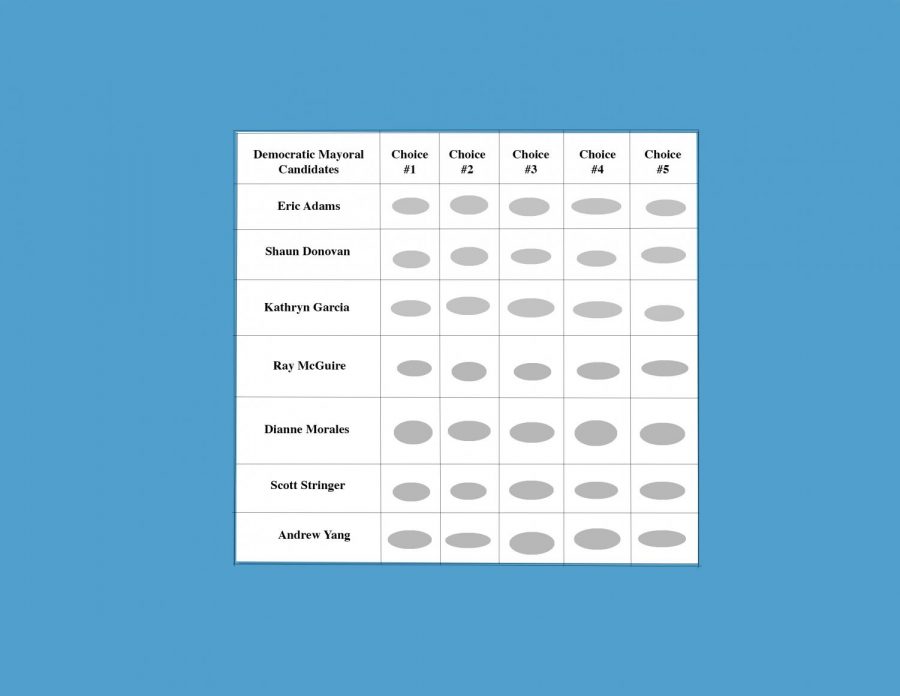

The way that ranked-choice voting works is that ballots have a chart that shows the list of all of the candidates on the left-hand side, with ranks listed horizontally along the top of the chart. There are five bubbles next to each candidate’s name so that people can choose to rank each candidate from one through five.

Voters only have to vote for one person, but they’re allowed to vote for up to five people. However, it’s more complex than it sounds.

A voter can only vote for one candidate one time, even though there are five bubbles next to each name. If a voter votes for one candidate more than once, such as for all five ranks, then it counts just as putting that candidate down for their first-choice candidate and not picking a second through fifth choice.

If a voter chooses more than one person for a single rank, such as voting for two people for first place, it invalidates the whole ballot.

Once the voting is done is when the really complicated part comes into play.

If no candidate wins more than 50% of the first-place votes right off the bat, then the ranked- choice voting process kicks in.

First, all of the first-place votes are compared and the candidate with the least number of first- choice votes gets eliminated. Then, the votes of all the people who chose said eliminated candidate as their first choice get reallocated to who each person chose as their second choice.

For example, if in the Democratic mayoral primary election, candidate Art Chang gets the least number of first-place votes, the votes of all the people who put him down as their first choice don’t get thrown out. Instead, the votes go to who each voter put down as their second choice. The process then repeats. After reallocating the votes that had been for Chang, the candidate who has the next least number of votes gets eliminated, let’s just say Aaron Foldenauer. Then, all of the ballots that had Foldenauer as their first choice get redistributed to all of the second choices on the ballots.

This process continues until there is a clear-cut winner, meaning someone with at least 51% of the vote, even if this means that the reallocation process has to continue until there are only two candidates left.

An outcome of this voting process is that the person who initially had the highest number of first-place votes might not end up being the winner at the end of the process.

While there are some benefits to ranked-choice voting, like each constituent getting more votes and the encouragement of more positive campaigning rather than negative advertisements and attacks, the cons outweigh the positives in this case.

The past year and a half to two years have been wild, filled with stress, change and heartbreak. The last thing people need now is to have to learn a whole new system of voting, especially when primary elections have such a low voter turnout as it is.

At an online event organized by City & State and Spectrum News’ NY1, “NY’s Path to Ranked Choice Voting: Queens Forum,” from Jan. 28, State Assembly Member Alicia Hyndman echoed this concern.

“I just think that this needs to be delayed, because we’re talking about enfranchising voters,” Hyndman, a Queens Democrat, said. “I think that this is disenfranchising people because it’s too much information. I’m not saying people can’t grasp the information — I have a very well- informed community that will get the information — but there’s a huge percentage of people who are not going to get this and who will go there, be confused and guess who they’re going to blame? They’re going to say, ‘The politicians are changing things again and they’re trying to take away my right.’ I’m telling you this is what is going to be said. So, as much as we can, we’ll educate, but I’m concerned that this is just too much, too fast, and that this is not going to achieve the desired effect.”

On top of the fact that these past couple of years have been nonstop crazy, introducing this new voting system is going to make it much, much harder for the elderly and for naturalized immigrants to vote.

For naturalized citizens who might have grown up in another country with an entirely different language and even alphabet, navigating the convoluted waters of New York City elections is probably difficult enough. Add in ranked-choice voting, a confusing system in its own, and this could potentially disenfranchise many immigrants from voting in city elections.

As for the elderly and older adults, it may be as simple as the saying, “You can’t teach an old dog new tricks.” While this absolutely is not true for every older person, it’s no lie that this system will complicate things for some New Yorkers who have been used to voting in one particular way for much of their lives.

This is not even to bring up people with visual and reading comprehension impairments that could complicate trying to use the system even further.

As Hyndman said at the virtual event, the whole goal as of right now should be enfranchising people and getting more people to vote — not preventing them from doing so.