Combining Asian subgroups distorts research findings

April 22, 2021

The recent violence and hateful rhetoric against the Asian American and Pacific Islander community have brought to light the centuries-old racism and oppression that these people face daily in the United States. One of the culprits responsible for this issue is the aggregation of “AAPI” in research studies.

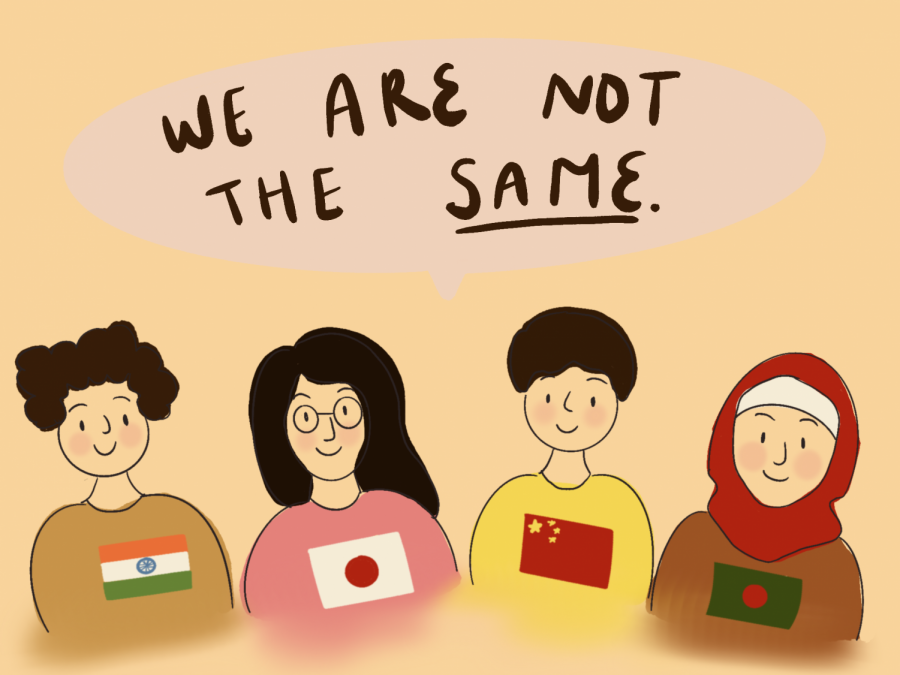

In the battle against racial injustice, what is often overlooked is how the Asian American and Pacific Islander Community is often lumped together as one homogenous group in social and scientific research studies. This issue goes hand in hand with the ever-present “model minority myth.”

The model minority myth is a social construct rooted in stereotypes specifically about Asian Americans, especially those pertaining to academic and financial success. As Professional Development Trainer Sarah-SoonLing Blackburn puts it, the model minority myth “characterizes Asian Americans as a polite, law-abiding group who have achieved a higher level of success than the general population through some combination of innate talent and pull-yourselves-up-by-your-bootstraps immigrant striving.”

The model minority myth operates on several levels, but the two most distinct are how it erases the blatant racism that the Asian American and Pacific Islander community faces, and how it pits Asian Americans against other oppressed racial groups within the United States.

What this myth suggests is that Asian Americans are a universally successful ethnic group who achieve socioeconomic success through hard work and innate intelligence. This implies that there is no reason why other groups of color cannot do the same, and thus places the responsibility on the oppressed rather than the oppressor.

This narrative is woven into how the Asian American community is represented in most research findings, especially those that focus on educational success or health-related issues. The vast majority of Asian American and Pacific Islander associated studies tend to favor the idea that East and South Asians are more inclined to academic and financial success, while either ignoring or misrepresenting the rest of Asia’s 48 countries and nearly all 15 of the Pacific Islands.

For instance, in a 2011 study entitled “Asian American and Pacific Islander Students: Equity and the Achievement Gap,” one million students of Asian American and Pacific Islander descent were academically compared to an indeterminate number of white students. However, this study labeled and focused on only eight different Asian ethnicities – Chinese, Korean, Vietnamese, Japanese, Indian, Filipino, Cambodian and Lao – and only two Pacific Islands – Hawaii and Samoa.

The categories “Other Asian” and “Other Pacific Islander” also made up a large quantity of the study, although the ethnicities in question were never specified.

The harm in generalizations displayed in studies such as these is that they massively underrepresent the Asian American and Pacific Islander community by taking the results of a few and applying them to the masses. The success of the East and South Asian students in this study was applied to all of East and South Asia, and the lacking results of Southeast Asian and Pacific Islander students were applied similarly.

It is important to remember that Asian Americans alone make up 5.6% of the United States population and that Asia itself makes up more than 59% of the global population. Attributing the academic success of a handful of students in one ethnic category to that of an entire continent’s worth of people is why such harmful stereotypes about Asians and Pacific Islanders continue to persist.

Anna Byon, an education-policy manager at the Southeast Asia Resource Action Center, highlights the root of the problem, claiming that the combining of “all AAPI students into one or two subgroups obscures cultural and historical differences that often shape students’ experiences and opportunities.” At its core, these generalizations are an erasure of Asian American and Pacific Islander culture.

Beyond academia, the community also suffers from a lack of representation in medical and scientific research. A recent case study found that among 1,077 articles published in high-impact generalist journals, only 263 identified Asians as a distinct ethnicity, with only 28 of these articles reporting outcomes for Asians and a mere nine including information about Asian subgroups. Pacific Islanders were not even mentioned.

The issue with many health-related studies is that they typically lump together separate ethnic groups as being Asian or Pacific Islander or do the opposite and hyperfixate on only one subgroup. Because of this practice, results for one group, or mass results for several groups, are incorrectly extrapolated to other Asian or Pacific Islander subgroups.

This leaves the community with an alarming degree of health disparities, such as how Asian Americans have the highest rate of undiagnosed diabetes within the United States.

Generalizing the Asian American and Pacific Islander population feeds back into the alarming amount of anti-Asian hate crimes currently occurring within the United States.

Asian Americans specifically have suffered from being seen as one homogenous race, with no distinction in terms of country, culture or language. It thus comes as no surprise that when China was wrongly accused of deliberately spreading COVID-19, hate crimes against not only Chinese Americans but also Korean, Vietnamese, Cambodian, Japanese and any other Asian-appearing Americans rose exponentially.

Disaggregating findings concerning Asian American and Pacific Islanders is only one part of the battle.

Reforming how research is conducted to properly represent the Asian American and Pacific Islander community involves dismantling the model minority myth, unlearning racist stereotypes and relearning how and why the community has been so disrespected and misrepresented in the United States. This is an issue that goes far beyond a few case studies but can no longer be tolerated.