People who are deaf and blind face new challenges amid the COVID-19 crisis

May 10, 2020

In the midst of the coronavirus pandemic, the disabled community has been neglected heavily. The blind and deaf have been particularly impacted by government guidelines insisting that citizens wear masks in public and social distance.

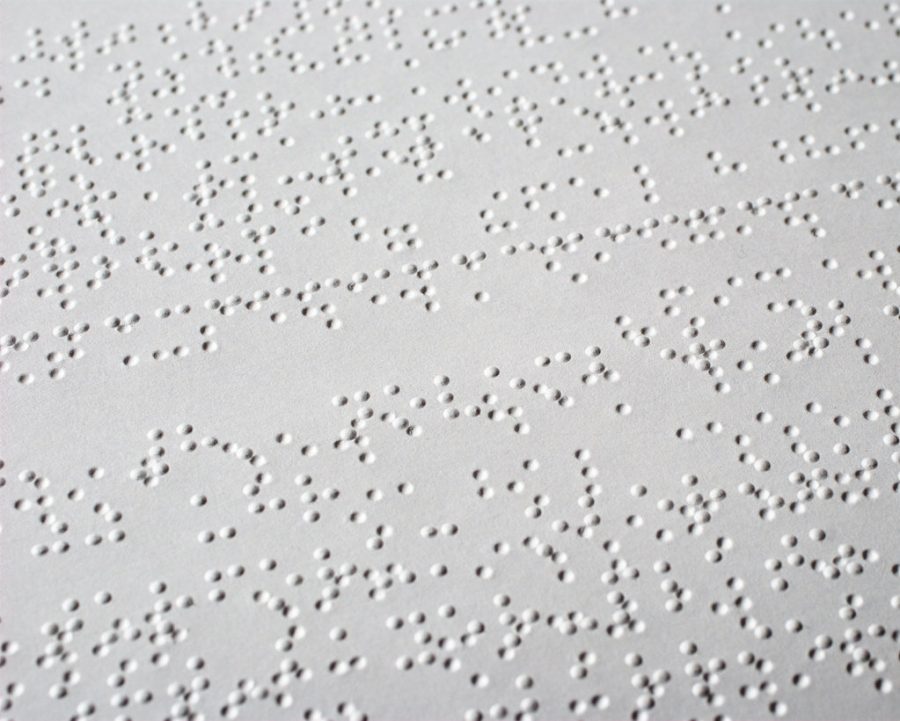

Many deaf individuals rely on some form of lip reading along with communicating through sign language in order to understand what others are saying. The use of face masks can become a barrier that prevents them from being able to easily communicate with other people. Additionally, social distancing guidelines could cause difficulty for those who are hearing-impaired since the increased distance between people can make it harder to hear. These social distancing guidelines also create challenges for the blind. Visually impaired people are finding themselves unable to touch items as they usually do because of new rules and employees who normally help them are advised to keep a distance from customers. Touching multiple items can increase the risk of contracting or spreading the coronavirus, but for many blind people, touch is how they navigate themselves within grocery stores.These changes are in place so that employees and customers do not become exposed to the virus, but it neglects a population without offering any alternatives. Though government restrictions are necessary to keep the coronavirus from spreading, they have made it more difficult for the disabled population to get aid entirely. “It has always been a challenge to get interpreters and services, but it seems like this virus has actually made it worse,” said Tony Wooden, ASL direct project supervisor at the Mayor’s Office for People with Disabilities, to NY1.

Disabled groups are worried that they are not being considered as a priority during the pandemic. These fears stem from the fact that they have been excluded from the list of those deemed most vulnerable to the coronavirus.

As a result, they are not being given priority in terms of hospital care. “As the number of COVID-19 cases and corresponding deaths accelerates across the country, one of America’s most vulnerable — and most overlooked — groups of citizens worry not just about how to get food and pay rent in a locked-down nation, but whether they will even be considered treatable if they get sick,”1 according to USA Today.

There may also be a stigma against the disabled community that they cannot be saved once they are officially diagnosed as well. This belief leads to implicit bias against them, in which the situation could occur where a hospital does not provide the best care for them.

This mindset is especially dangerous to harbor during the current global pandemic. Patients diagnosed as having disabilities fear that hospitals will choose to save someone’s life over theirs . Considering “rationing guidelines in Alabama, Kansas, Tennessee, and Washington State allow doctors to withhold care from people with disabilities in violation of federal law,” it is understandable why patients with disabilities are concerned, according to The Atlantic.

Another issue arises when battling shortages; those with disabilities are considered to not be the forefront citizens for what supplies are available. In a statement released by Alabama Department of Public Health, those with “severe mental retardation … may be poor candidates,” for a ventilator if hospitals run short during this pandemic.

Some states have already allowed hospitals to withhold life sustaining equipment from those with disabilities. For example, hospitals with shortages are currently allowed to repeal ventilators from patients who normally use them to breathe and give them to coronavirus patients instead.

These policies, however, have mostly gone unnoticed as the public has not been made privy to this knowledge. Regardless, some disability advocates have spoken out, claiming that judging whether a person should be cared for or not based on “patients’ expected lifespan; need for resources, such as home oxygen; or specific diagnoses, such as dementia,” is inhumane and not fair, according to the Center for Political Integrity.

As the coronavirus pandemic continues to spread, it’s important to take into account populations that can experience increased difficulty and treat them as equals. Prioritizing lives within hospitals based on whether an individual has a disability is inhumane and unfair, and more has to be done to make the world more inclusive for these populations.