In a recent study, researchers from the Hebrew University of Jerusalem compared how artificial intelligence models and the human brain learn spoken language and found similarities, suggesting that the brain learns language by applying context to new words rather than traditional grammar rules.

This implies that language is learned through a gradual and systemic process of learning sounds, words and finally sentences.

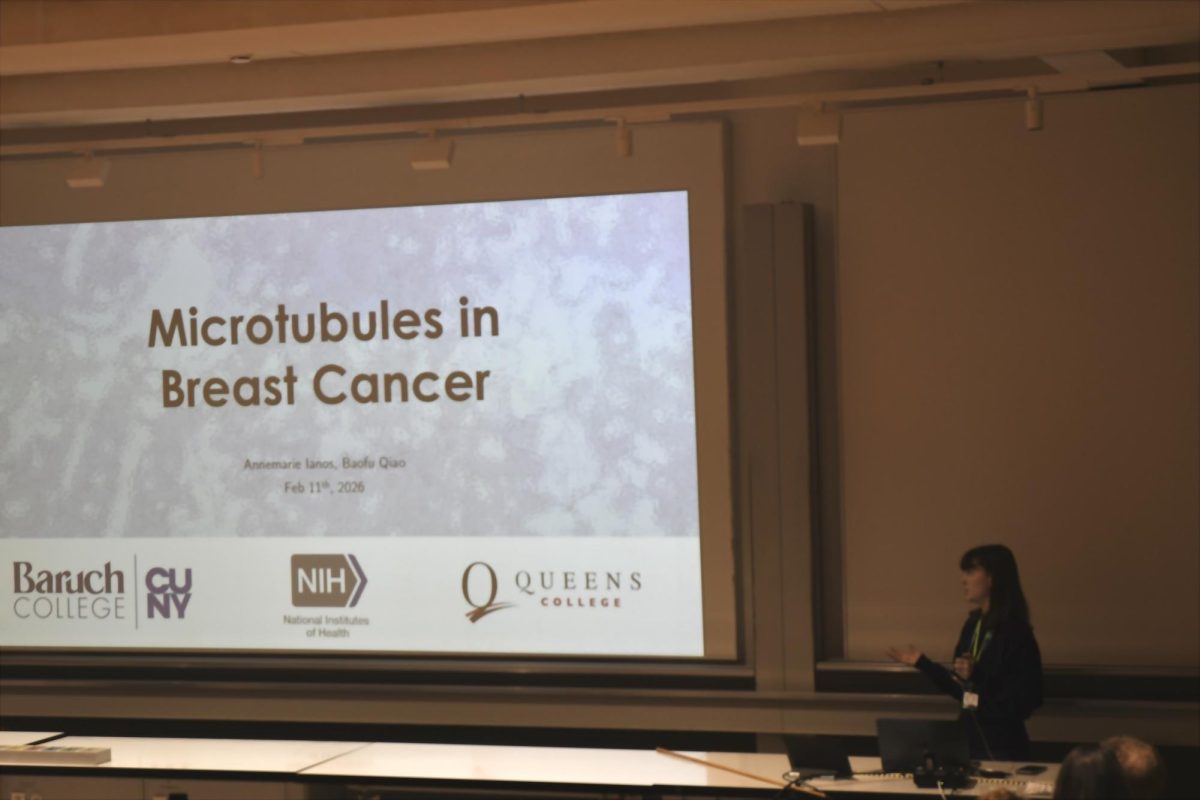

The study included nine epileptic patients who listened to 30 minutes of “Monkey in the Middle” from NPR.

Researchers also played a podcast created by large language models.

LLMs work by encoding words and context into numerical data known as embeddings. They have three key functions: embedding context into words learned, predicting the next word and identifying errors to adjust corrections.

The LLMs used were GPT-2 XL, which consists of 48 layers, and Llama-2, which has 32 layers. Researchers also used classical methods to understand and categorize phonemes, morphemes, syntax and semantics.

To measure brain responses, electrocochleography was used to look at language learning regions such as Broca’s area.

Researchers tested the time the LLMs picked up words by looking at the time before and after words were heard.

After running the ECoGs, they analyzed and compared the results to GPT-2 XL and Llama-2’s comprehension of “Monkey in the Middle.”

Researchers found similarities in both LLMs and the patients. In predicting brain activity, the middle layers of the models had the best accuracy. Early layers stored simple information while deeper layers stored more complex meaning, suggesting that language is processed over time.

However, classical methods were not as effective as LLMs in measuring real-time brain activity.

Compared with the LLMs, classical methods were not as useful because they did not rely on previous information to generate outcomes. Their meanings were fixed, and as a result, they could not determine the meaning of words as the LLMs did.

Unlike classical methods, LLMs build layers that mimic the way the human brain comprehends speech. Neuroscientist Ariel Goldstein, who led the experiment, perceived the LLMs as a beneficial tool to further understand how our brains comprehend speech.

“What surprised us most was how closely the brain’s temporal unfolding of meaning matches the sequence of transformations inside large language models.

Even though these systems are built very differently, both seem to converge on a similar step-by-step buildup toward understanding,” Goldstein said.

While the LLMs suggest that the way we learn a language involves more context rather than learning through a series of hierarchy and symbolic structure, they are still flawed because they do not fully replicate brain function.