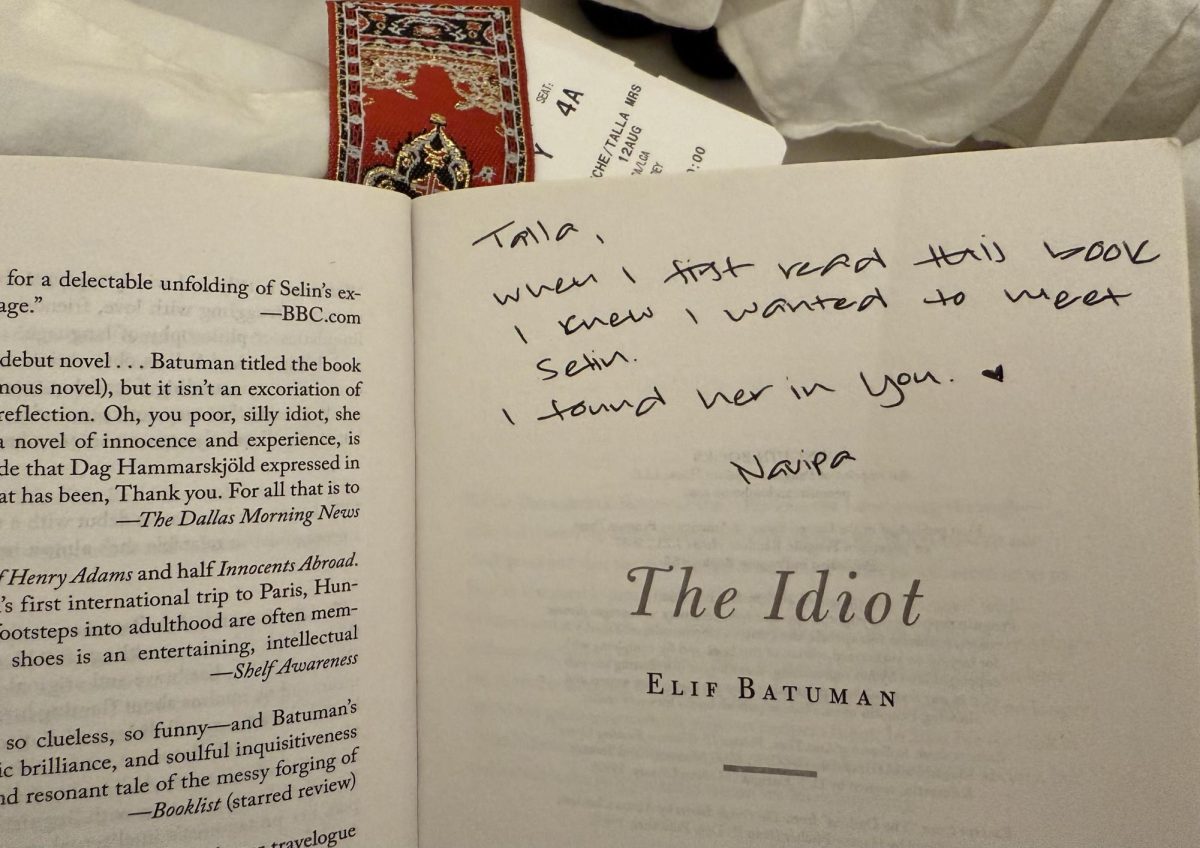

“The Idiot” by Elif Batuman follows Selin, an upper-class Turkish American freshman from New Jersey, as she begins her studies at Harvard University. The first half of the novel takes place on campus, where we are introduced to Selin’s suitemates and close friends Svetlana and Emmanuel. We also meet Ivan, a Hungarian upperclassman studying mathematics and preparing for graduate school.

Selin and Ivan meet in a Russian class where the curriculum revolves around an elementary textbook featuring a dialogue between two characters, Nina and Ivan, who are getting to know one another.

Batuman draws a parallel between the exchanges in the textbook and the conversations that unfold between Selin and the real Ivan. Selin is repeatedly frustrated with the textbook’s contrived plot and grammatical simplicity, projecting her irritation onto her own faltering conversations with Ivan and forgetting that the purpose of the textbook’s dialogue is linguistic precision rather than intimacy or emotional connection. As emails emerge and Ivan travels to visit graduate programs, the barrier between them widens.

Their exchanges over email contrast with the simplicity of their in-class dialogues; the boldness they achieve in writing transforms Selin’s sense of what language can do. Language becomes a site where desire and comprehension are both constructed and deferred, an instability that fuels much of Selin’s anxiety.

Selin’s dependence on email as her primary form of connection does not merely mirror her intellectual curiosity; it exemplifies the notion of a “hybrid subject” shaped as much by the technological apparatus through which she speaks as by her own intentions.

When Selin eventually seeks counseling, she is told, “All of this leaves you terribly lonely and isolated, which I think explains your susceptibility to this computer fellow. He seems to be offering you just what you want, a noninterpersonal interpersonal relationship.”

This is not to suggest that the author, Batuman, valorizes in-person interactions as the sole form of connection. Selin calls her mother frequently, and there are moments when she says nothing and feels fully understood across borders. Even after Ivan returns to Boston and they meet in person, he and Selin struggle to articulate themselves, and the gaps in communication foster frustration and hostility.

By the end of the first part of the novel, Selin’s observations about the women in the novels she reads, the parties she attends and even in “The Story of Nina,” which is about obsessing over a man, come back to haunt her. She finds herself similarly consumed with decoding Ivan.

Batuman addresses a broader anxiety intrinsic to the passage into adulthood: the simultaneous fascination with and reluctance to let romantic attachments occupy a central place in a young woman’s life, especially during the golden age of independence.

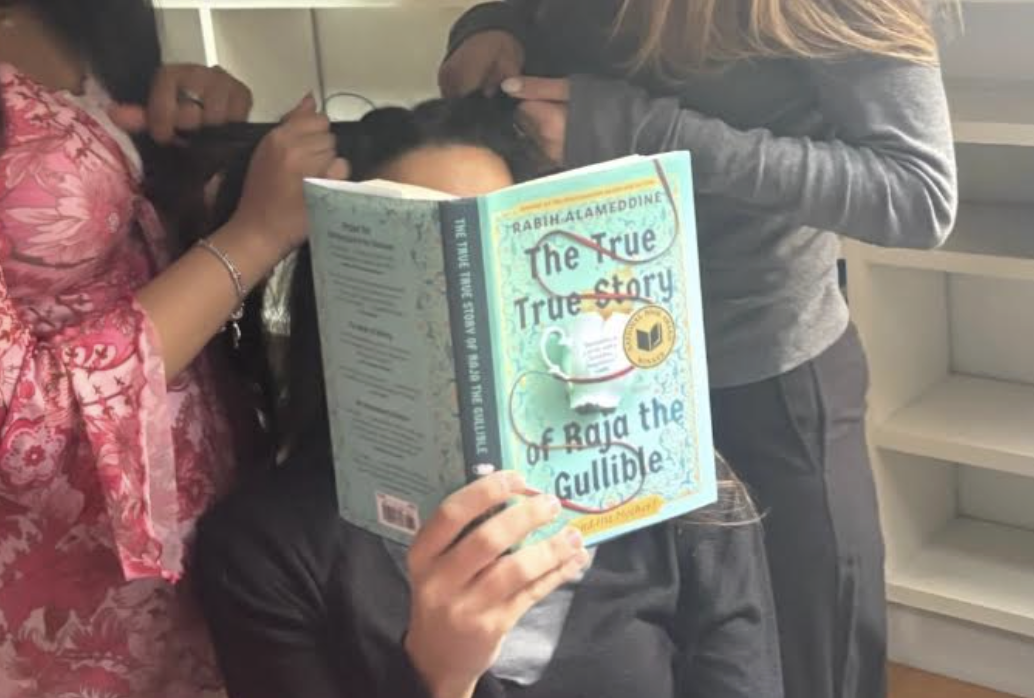

Selin’s relationship with language is further explored through her independent pursuits in teaching, echoing the adage that one never truly understands something until they can teach it. During the second half of the novel, Selin travels across Europe and her adaptability comes into focus. She easily moves between environments and finds ways to connect with people across cultural and linguistic boundaries.

One can imagine how differently her story might have unfolded had she gone to New York to work at a publishing house instead of teaching Hungarian children in a rural village, or if she had tutored college students in math rather than teaching basic algebra to adults who never finished high school. These experiences forced Selin to translate ideas that feel intuitive into language deliberate enough for others to understand.

Throughout the novel, Batuman employs stream-of-consciousness narration, presenting Selin’s intellectual reflections as immediate with a shrewdness that naivety never fully registers.

The novel engages with language, culture as rooted in place, the ways our thoughts shift across the languages we know and the narratives we construct through class and aesthetics.

Like all art, one grows fonder of this novel after grasping the author’s intention. The novel is not particularly plot-driven through a series of semesters; instead, language itself becomes the focal point. Selin’s naiveté, far from a narrative weakness, is what propels the reader forward. Her curiosity sustains the narrative even when certainty eludes her.

As Selin completes her school year, she reflects, “I hadn’t learned what I had wanted to about how language worked. I hadn’t learned anything at all.”

The novel’s ending is especially resonant as Selin remains in college, not just pursuing an academic career, but striving to understand how her experiences are influenced by language.