Cats may doze through the day, but their aging brains could wake us up to Alzheimer’s puzzle. A new study from the University of Edinburgh suggests that the answer may lie not only in humans, but also in cats. Researchers discovered that older cats with dementia show the same toxic brain changes seen in people with Alzheimer’s disease: buildup of amyloid-beta proteins and the loss of vital synapses. These are the connections that allow brain cells to communicate.

Amyloid-beta is a sticky protein fragment that clumps together between brain cells. It’s harmless in small amounts, but when too much accumulates, it disrupts communication and triggers cell damage. Think of it like weeds spreading across a garden — if left unchecked, they choke the pathways that keep everything alive.

Researchers have long wondered what triggers this buildup. In humans, poor sleep is one known factor. During deep sleep, the brain clears out waste proteins, much like gardeners tending the soil overnight.

When this process is disrupted, amyloid-beta piles up like invasive weeds, suffocating synapses and impairing memory. In cats, the exact mechanism is not clear yet.

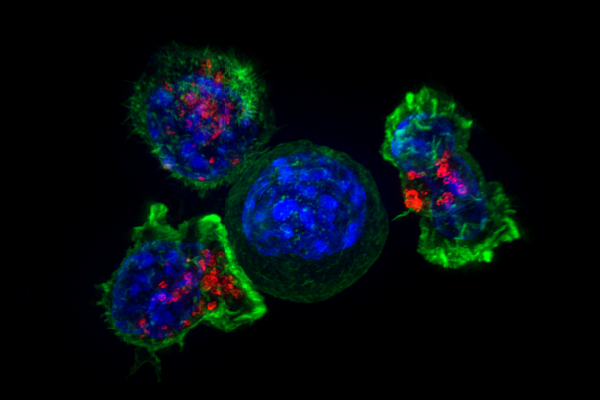

Despite their famously long naps, their brains can still grow the same dangerous tangles. To better understand this process, the Edinburgh team examined the brains of 25 cats of various ages who had passed away, including those showing signs of dementia. Using powerful microscopes, they found amyloid-beta clustering right inside the synapses.

These tiny bridges are essential for transmitting messages across the brain. Their loss is strongly tied to memory decline in people with Alzheimer’s. The study also revealed something even more striking. Brain support cells, which are astrocytes that nourish and stabilize neurons and microglia, were observed ‘devouring’ the damaged synapses.

This process, called synaptic pruning, is similar to gardeners trimming excess branches to keep the brain healthy during development. But in aging brains, these gardeners can become overzealous. Instead of protecting the system, they start cutting away too much, leaving the neural landscape bare and fragile.

In essence, amyloid-beta poisons the bridges, the gardeners sense the damage and in trying to repair the garden, they may accelerate its decline. A recent experiment with living human brain slices confirmed that amyloid-beta from Alzheimer’s patients is directly toxic to synapses.

This matters because the classic lab rat has never lost its memory to dementia. Scientists must artificially engineer Alzheimer’s-like conditions in them, which doesn’t fully capture the complexity of the disease. Cats, on the other hand, develop it naturally as they age, making them far better models for studying how the disease progresses and for testing therapies that could work for both species.

Professor Danièlle Gunn-Moore, a feline medicine expert at Edinburgh’s Royal School of Veterinary Studies, emphasized the significance. “Feline dementia is so distressing for the cat and for its person,” Gunn-Moore said in a press release. “It is by undertaking studies like this that we will understand how best to treat them. This will be wonderful for the cats, their owners, people with Alzheimer’s and their loved ones.”

For cat owners, the research also highlights signs worth watching for: confusion, changes in sleeping or eating habits, less grooming or altered social behavior. Experts estimate that more than a third of cats over the age of 11 may show at least one sign of cognitive decline, underscoring the importance of awareness.

Looking forward, the findings suggest a shared path for human and veterinary medicine. If researchers can stop the toxic weeds from spreading and guide the gardeners to prune wisely, those same breakthroughs could unlock treatments for over 55 million people living with dementia today — a number that’s expected to triple by 2050.

Categories:

Cats with dementia could help unlock the Alzheimer’s puzzle

August 25, 2025

More to Discover