In honor of his newly released book series, “Dear New York,” photographer and writer Brandon Stanton turned Grand Central Terminal into an immersive exhibit, full of photos from his 15-year-old archive.

Stanton moved to New York City and created his Humans of New York photoblog in 2010. What started as merely photos of New Yorkers soon became more personal as he implemented little quotes into the blog.

Stanton’s popularity rose when the age of social media began. By 2013, he published his first book that instantly became a New York Times No. 1 best-seller. In 2015, he became the first social media creator to interview and photograph the U.S. president in the Oval Office during the Obama administration.

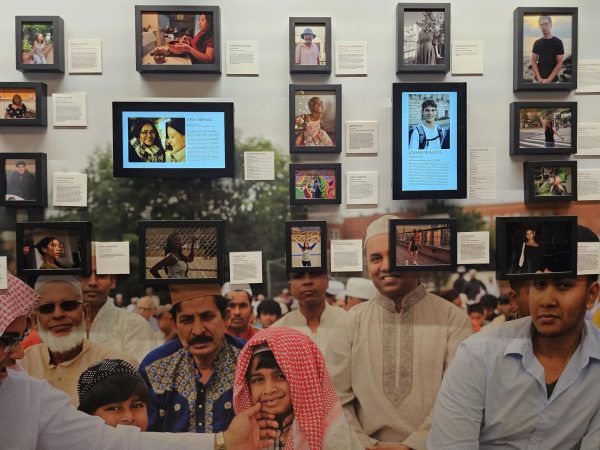

From Oct. 6 through Oct. 19, Grand Central removed all advertisements in the building for the first time, replacing them with photos and stories of thousands of different New Yorkers. The cost visitors paid to view the exhibit was equal to the subway fare: $2.90.

In this exhibit, New York is described as representing humanity itself. Stanton drew inspiration from the city’s vast diversity of cultures, religions and beliefs.

“And all of us crowded onto the same narrow sidewalks, the same one-way streets, the same subway cars,” he said in a statement. “With all of these differences packed into such a small place, it’s a miracle that this city works. Yet somehow, despite the honking, the screaming, the shoving, the cursing; we make it work.”

Stanton said in an interview that the exhibit is not about earning money. The profit he received from the book sales directly funded the installation, and any extra proceeds would be donated back to charities, “so it’s designed to be an artistic and financial gift to the city.”

On top of paying to use the space, Stanton also had to cover any revenue Grand Central lost from not displaying those advertisements for the two weeks the exhibit was on display.

David Korins, known for his set design on Broadway shows, acted as the creative director of the exhibit experience. Korins said the design plan was to engulf people without bombarding them. “We want this to wash over you like a meditation. For some people it’ll be a mirror; for others, a portal into deep empathy,” Korins said.

The main concourse featured 50-foot projections on the walls, displaying different faces and quotes. The Juilliard School students and alumni played on a Steinway Model D concert grand piano in the very center of the concourse during off-peak hours, and Stanton opened paid one-hour “shifts” to other New York pianists.

On Oct. 10, Whitney Guo Szakacs, a 6-year-old girl who could not even reach the pedals, played the piano for all the visitors and commuters to hear. According to the Humans of New York Instagram account, she played the one song she knew: Anton Diabelli’s “Sonatina No. 1 in F major.” According to a social media post, Guo Szakacs told Stanton, “In the beginning, it was scary. But it wasn’t scary at the end, because it was all done.”

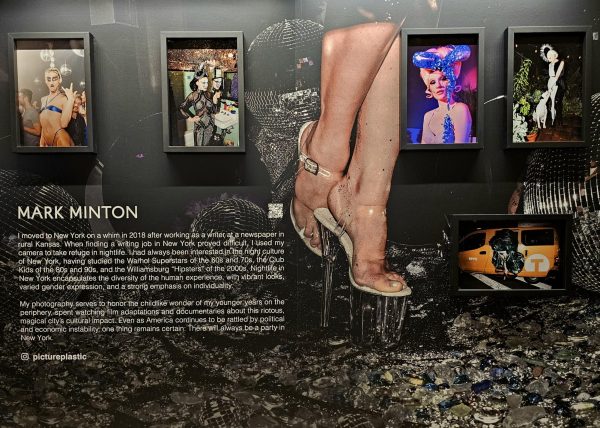

The Vanderbilt Hall was transformed into a community showcase of different artists. Over 600 schoolchildren were given the opportunity to showcase their photography, prompted to “photograph and write about someone in their community who has made an impact.”

Ten experienced photographers were also given $10,000 in grants to facilitate their work in the hall. The subway station had large vinyls plastered on every wall leading to the platforms, starting on the sides of the turnstile.

“It represents the largest and most customized vinyl installation in the history of the subway system—either commercial or artistic,” advertising company OUTFRONT Media said in a LinkedIn post.

The subway portion was designed by Andrea Trabucco-Campos. He said that to figure out the design, he and his team had built 3D models of different sections to map out the corridors and all the different entry and exit points. Trabucco-Campos explained how people needed to be able to understand the story no matter what point they started from, meaning it could not be linear.

The Metropolitan Transportation Authority described this section of the exhibit as “the most extensive use of physical subway space in its history.”

After the exhibit ends, Stanton’s book will remain as the only piece of his love letter to the city.