Scientists at Scripps Research identified an unusually active region of the brain linked to alcohol withdrawal symptoms in animals, offering new insights into the early mechanisms that drive relapse cycles.

Relapse is the continuous dependence on alcohol that is developed not for pleasure, but for relief. “What makes addiction so hard to break is that people aren’t simply chasing a high,” Friedbert Weiss, a professor of neuroscience at Scripps Research said.

“They’re also trying to get rid of powerful negative states, like the stress and anxiety of withdrawal.”

Within the U.S., over 10 million people struggle with alcohol use disorder, many of whom feel misrepresented, misunderstood and unsupported in their search for effective treatment.

In addressing relapse, what’s often overlooked are the root causes, or the underlying psychological and neurological factors.

Because this study primarily focuses on the brain, it offers hope that future treatments may finally target the deeper causes.

To uncover the workings of withdrawals, scientists studied rats by conditioning them through the process of operant conditioning, a learning process where behavior is shaped by rewards or punishment.

Rats that were given alcohol initially associated it with a reward and a feeling of pleasure.

However, following multiple cycles of withdrawal and relapse, this association began to shift toward relief instead.

Simultaneously, the association grew stronger, further reinforcing the rats’ desire for alcohol.

The rats learned to link alcohol with easing withdrawals and relapses: a type of operant conditioning known as negative reinforcement.

Rats driven by this negative reinforcement found themselves going to great lengths to obtain alcohol.

“These rats seek alcohol even if that behavior is punished,” Weiss said.

The same pattern can be seen in people, where the drive for relief or habit disrupts them from reflecting their true choices.

This study shows that addiction is where the absence of free will is most common.

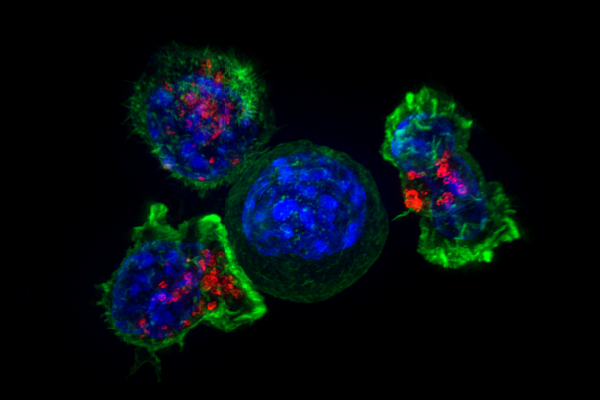

In analyzing the brains of the rats, scientists separated them into four groups: one that had developed the alcohol-relief association and three control groups that had not.

Using precise imaging tools, scientists found that in the group of rats that formed the association, the paraventricular nucleus of the thalamus, an area tied to stress and emotional regulation, stood out the most for its increased activity.

While much is still unknown about how to fully treat relapse, this study sheds light on where in the brain these processes take place.

“This study shows us where in the brain that learning takes root, which is a step forward,” Weiss said.

These findings can be applied to the broader mental health continuum, offering new ways to understand and eventually treat behavioral conditions like anxiety.