The research team, led by Dr. Gawon Cho, a postdoctoral associate at the Yale School of Medicine, studied 270 individuals over a span of 13 to 17 years.

Each participant underwent an overnight sleep study — called polysomnography — to measure the proportions of different sleep stages.

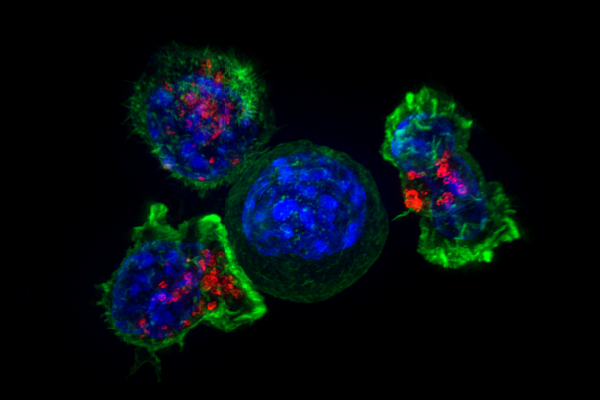

More than a decade later, MRI scans of the volunteers’ brains revealed something striking: participants who spent less time in SWS and REM had smaller volumes in areas like the inferior parietal region, cuneus and precuneus, which are known to be at risk in early AD.

SWS, often called “deep sleep,” is when your body handles much of its nightly repair work — ranging from tissue growth to hormone release — while your brain clears out waste.

REM sleep, on the other hand, is closely tied to memory consolidation and emotional processing. According to Dr. Cho, “Our findings provide preliminary evidence that reduced neuroactivity during sleep may contribute to brain atrophy, thereby potentially increasing the risk of Alzheimer’s disease.”

Although many earlier studies hinted that not enough sleep can heighten dementia risk, this new work adds precision: which parts of the sleep cycle seem most protective and where in the brain these deficits show up. The fact that the inferior parietal region — often the site of early AD-related changes — appears significantly smaller in people with reduced SWS and REM underscores the possibility that targeted sleep interventions might keep brains healthier longer.

Scientists and clinicians have long been searching for ways to delay or prevent Alzheimer’s, which currently affects an estimated 6.9 million Americans aged 65 and older. “Sleep architecture may be a modifiable risk factor for Alzheimer’s disease and related dementias, posing the opportunity to explore interventions to reduce risk or delay Alzheimer’s onset,” Dr. Cho emphasized.

In other words, ensuring you get enough deep and REM sleep could eventually join diet and exercise as part of a prescription for better cognitive aging.

It is worth noting that none of the participants had dementia or significant stroke history when the study began. Even so, the differences in brain volume emerged clearly later, linking shortfalls in deep or REM sleep to potential risk pathways for AD. As Dr. Cho and colleagues pointed out, more research is needed to unravel the causal chain.

In the meantime, if you frequently deprive yourself of sleep, consider that these findings might be a warning sign that you need to prioritize a full night’s rest.

From bench to bedside, the takeaway is straightforward: healthy sleep habits could be a practical avenue for reducing AD risk. As the study’s results make clear, the way sleep is structured — beyond just the total number of hours — matters greatly.

While it might feel tough to adjust sleep schedules, the promise of preserving precious brain tissue and potentially delaying a devastating disease like AD makes a compelling case for turning out the lights a bit earlier and making every stage of sleep count