A deadly strain of avian flu has reached mainland Antarctica, killing off penguins and other wildlife.

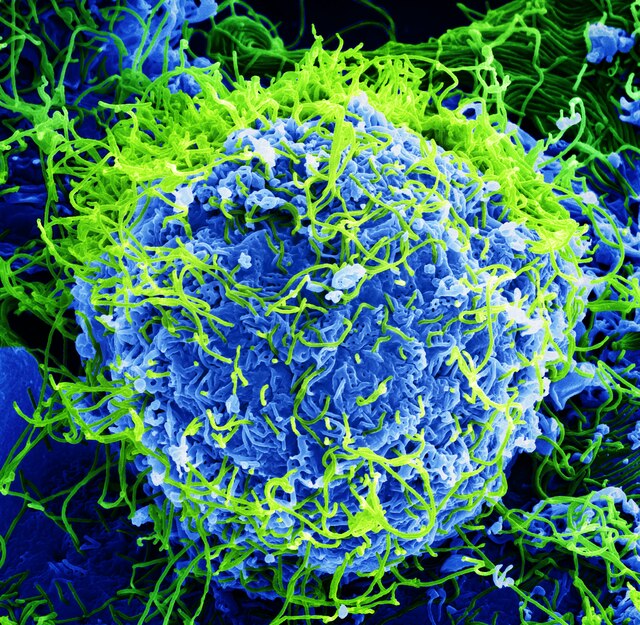

Researchers initially confirmed the presence of the virus in dead seabirds near an Argentine base in Antarctica on Feb. 25. “This discovery demonstrates for the first time that the highly pathogenic avian influenza virus has reached Antarctica, despite the distance and natural barriers that separate it from other continents,” the authors wrote.

This current H5N1 outbreak started in 2021 and is thought to have killed millions of birds already.

The virus killed over 200,000 birds in Peru when it reached South America. It has now reached every continent except Oceania. With it now spreading to mainland Antarctica, this marks a giant leap in the level of destruction the virus can enact.

The virus has been carried across the globe via the migratory patterns of various species of birds. It has torn through both domestic and wild animal populations. Millions of chickens and other poultry birds have died from the virus, posing a high economic cost on top of the already devastating ecological cost.

The virus has even spread from birds to mammals, notably affecting elephant seals and even one polar bear. At least 320 types of birds and dozens of species of mammals have been affected. The extent of the devastation caused by this panzootic virus is raising alarms when it comes to extinction and ecosystem collapse.

Penguins, in particular, are considered very susceptible to the deadly virus.

Penguins are known to huddle tightly, which scientists expect will make it easier for the virus to spread amongst them. It is also expected that their natural immunity will be lower than in other bird species since they had been relatively isolated from the virus before now. Dense populations and low immunity are an ideal breeding ground for the virus.

Humans are not normally affected by bird flu, but close, prolonged contact may make it more likely. Some wildlife sites have been closed to limit the spread of the virus but there’s not much else to be done.

“Nothing more can be done to limit transmission in wildlife and the outbreak will have to resolve naturally,” said Matthew Dryden from the UK Health Security Agency.

The Antarctic Wildlife Health Network has established a database to record and monitor all suspected outbreaks of the virus.