A recent analysis of artifacts in a Berlin Museum revealed a complex adhesive used to make tools, indicating that Neanderthals were more intelligent and had more cultural development than once believed.

The report, published in Science Advances, looked at findings from Le Moustier, an archeological site in France from the early 20th century. The stone tools from this site were dated between 120,000 and 40,000 years ago, almost the same time span as the Neanderthals. They were initially considered unremarkable, but a recent internal review of the collection brought the tools to the forefront of scientific inquiry.

“The items had been individually wrapped and untouched since the 1960s,” Eva Dutkiewicz of the Museum of Prehistory and Early History at the National Museums in Berlin and co-author of the study said. “As a result, the adhering remains of organic substances were very well preserved.”

Past knowledge showed that Neanderthals made glue out of birch tar, something Homo sapiens started doing around the same time. However, ocher-based complex glues were previously only ever recorded in H. sapiens in Africa, not the Neanderthals of Europe.

Ocher is a natural clay pigment that formed the basis of this newly found glue. Neanderthals added bitumen, a component of crude oil, to the mix.

Researchers were surprised with how much ocher was added to the bitumen as air-dried bitumen could be used as an adhesive without any ocher, but too high of an ocher content would strip the bitumen of its adhesive properties.

The researchers then made their tools using ocher and bitumen and found that a 55% ocher content was just enough to form a mass that could stick to the stone tools without sticking to hands, making it ideal for a handle.

The study’s authors also noted that ocher and bitumen had to be collected far from the Le Moustier region, showing that a considerable amount of planning and complex cognitive and cultural patterns produced these tools.

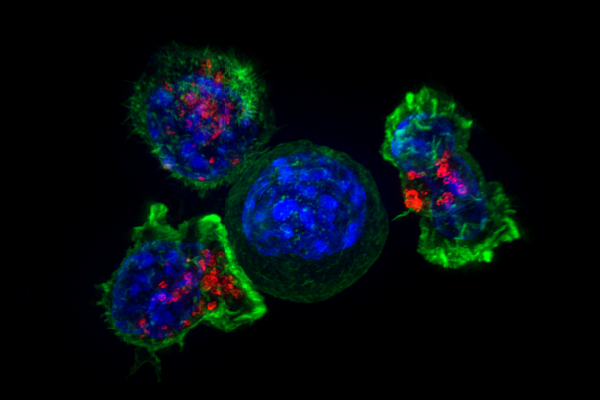

“Compound adhesives are considered to be among the first expressions of the modern cognitive processes that are still active today,” Patrick Schmidt from the University of Tübingen’s Early Prehistory and Quaternary Ecology section and first author of the study said.

“What our study shows is that early Homo sapiens in Africa and Neanderthals in Europe had similar thought patterns,” Schmidt added. “Their adhesive technologies have the same significance for our understanding of human evolution.”