It’s hard not to see the parallels between Broadway musicals Hadestown and Hamilton: the two started off as concept albums, had world premieres in New York and within a few years, made it onto Broadway, garnering over a dozen Tony nominations.

They each take old tales that are part of the fundamental Western storytelling mythos and adapt them into creative, fresh takes on the material.

Nothing will likely match the cultural phenomenon of Hamilton any time soon, but with 14 Tony nominations in less than two weeks after opening on Broadway, Hadestown has proven itself enough as a show that should be seen while tickets are still available.

Hadestown, Anaïs Mitchell’s neo-folk musical, tells the story of doomed lovers Orpheus and Eurydice — from one of the better-known Greek myths — relative to the May-December romance between Hades and Persephone, which is really more of an April-September thing, as Persephone alternates half-years between being on Earth and being with her husband, lord of the underworld.

Constructed as something akin to magical realism, Hadestown acknowledges the fact that it takes place in a “world of gods and men,” while avoiding much show of mythological power.

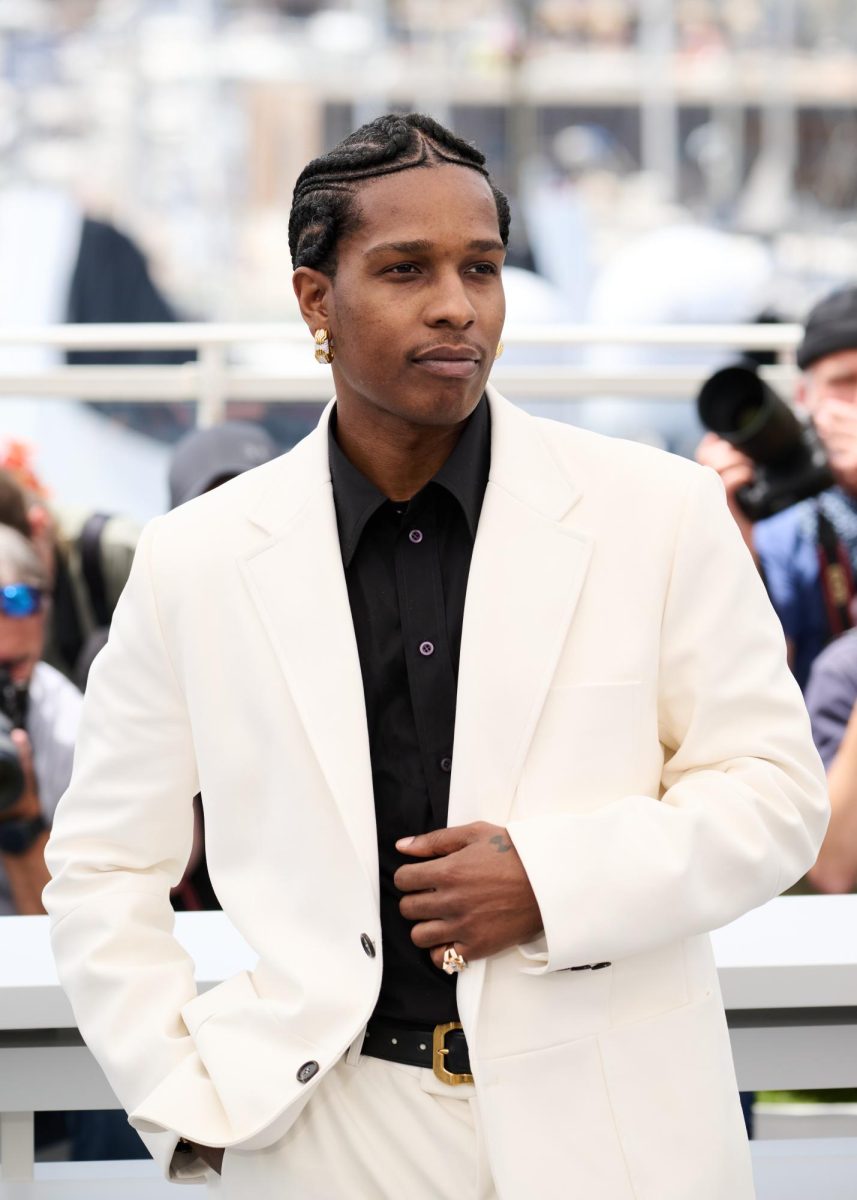

Hermes, the messenger god and narrator of the story, is played by the magnificently worldly André De Shields, sporting tasseled elbows in place of winged feet.

Along with De Shields, the entire principle cast is at the top of their game. As Orpheus, Reeve Carney perfectly embodies the soulful, penniless poet and musician working on a song to bring back spring.

Opposite Carney is Eva Noblezada, playing the tragic Eurydice, poignantly struggling with hunger as her husband doesn’t notice her suffering.

Their relationship certainly has its high points, but it’s also made up of isolated moments through which the two characters’ failing love can be romanticized.

A lot of the fun to be had in Hadestown is with its big, brassy numbers, especially as sung by the Fates — the three destiny-controlling goddesses played by Jewelle Blackman, Yvette Gonzalez-Nacer and Kay Trinidad.

Songs like “Way Down Hadestown” and “When the Chips Are Down” are great examples of the New Orleans-style sound the retelling has to offer. The Fates are cruel, but they’re not bad guys, and when they take away food, clothing and shelter, their smirking, swaggering roles are enough to enamor them to any audience.

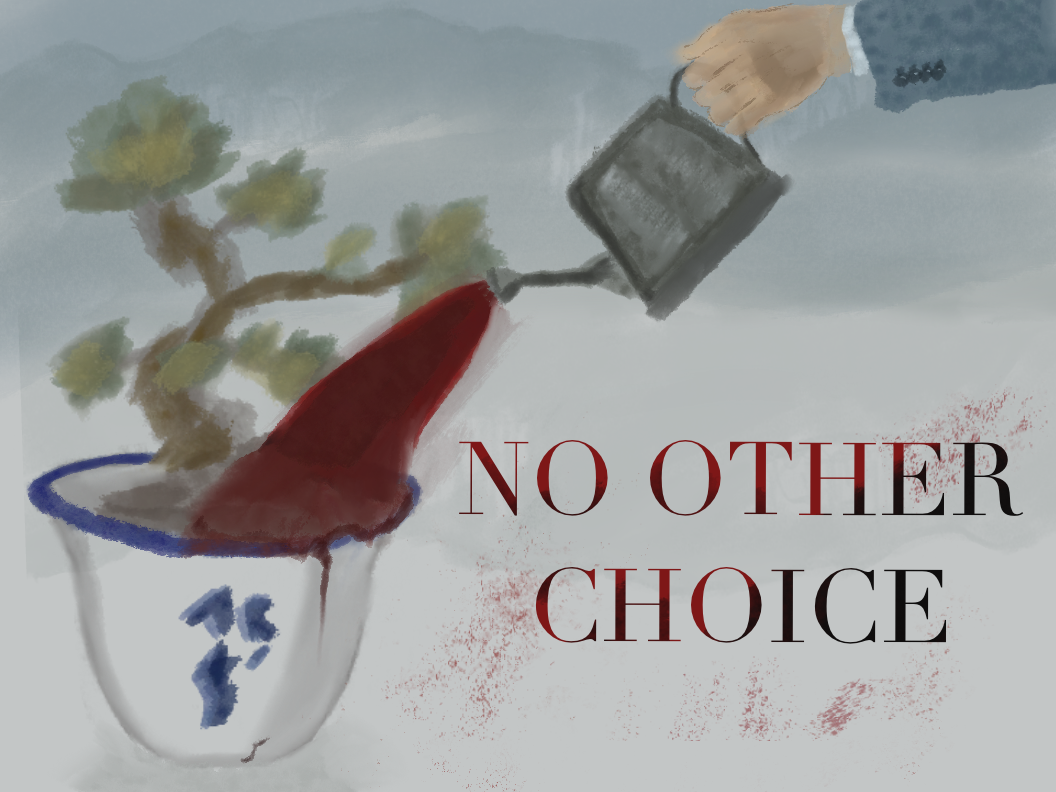

Couched in dehumanizing, capitalist language, Hades offers Faustian bargains to those who are starving, with contracts that turn humans into unnamed, soot-covered labor forces.

The big finale to Act I is the song “Why We Build the Wall,” and whether the message was originally written as a reference to the aspirations of the current U.S. president, the whole social struggle of the show feels ham-fisted.

Patrick Page’s portrayal of Hades toes the line of camp, with exaggerated deliveries that sound like imitations of Ivan Moody singing Five Finger Death Punch’s cover of “House of the Rising Sun.”

In his leather jacket and sunglasses, Hades cuts an impressive figure sitting and watching the action unfold from a balcony tavern seat when the show opens, but the more he talks, the less imposing he seems.

The real power of darkness is in Bradley King’s lighting design, at its strongest when the lights go down and lanterns haunt the stage.

Hadestown stays in memory because of its moments. As Persephone, Amber Gray takes over the stage with a brash roughness, especially in a song like “Our Lady of the Underground.”

In the appearances of the show’s symbolic red flower, the songs from Orpheus that harken back to romances of old there is a heightening of story, haunting long after the last bow.

The show socks no emotional punch with Orpheus’ climactic, love-dooming turn-around — an element of the myth that has to be a part of any telling — but the songs that bookend the moment do.

Hermes sings about the way the myth will be told over and over despite how much it hurts. There’s something missing in the emotions of it all, but it still feels old, timeless and meaningful.

Hadestown has a life in it that goes beyond the ancient, translated verse of Greek mythology. It’s not just because of the band members on stage that the music feels alive.

Hadestown has a story that resonates even for the least Greek-literate out there, and it’s got plenty of fun to be had.