Researchers in China have studied a genetic mutation’s impact on the gene for Monoamine Oxidase-A. A distinct mutated variation that does not change the exact proteins coding for the gene, still proved to have an impact on its function. In the mice studied, those that had one version of the variation showed higher gene expression, while those with another showed more unstable gene activity. This small mutation could have large implications on brain activity.

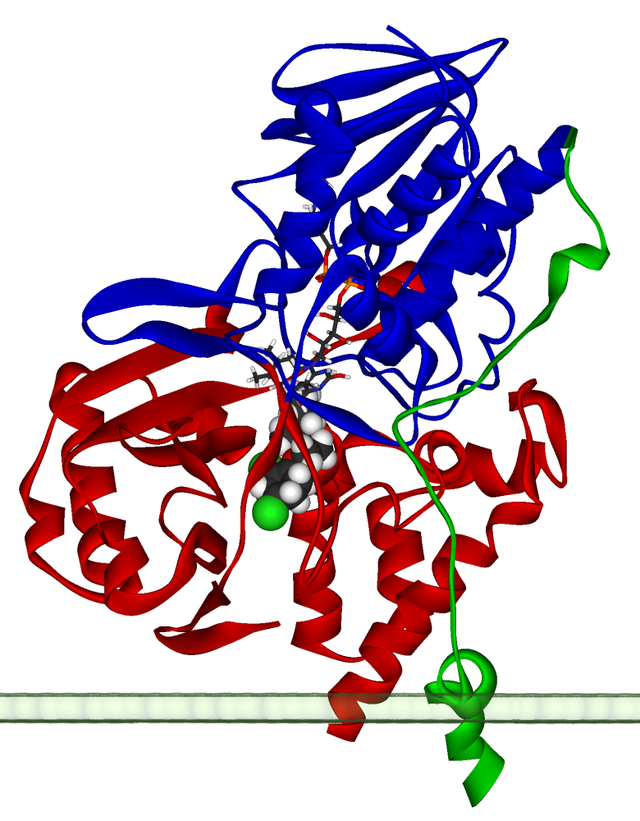

Often referred to as the “warrior gene,” the MAO-A gene is essential for controlling impulsivity and violence. In the brain, neurotransmitters including serotonin, dopamine and norepinephrine are broken down by the enzyme MAO-A, which is encoded by this gene.

Aggression is one of several behaviors that have been connected to imbalances in these neurotransmitters. Developing tailored therapies for those at risk of violent behavior requires an understanding of the genetic effect of MAO-A on aggressive behavior before moving forward.

The impact of the MAO-A gene on aggressiveness in genetically engineered mice was investigated in a 2021 study published in Nature Neuroscience. The study, led by experts from the University of Tokyo, concentrated on the Ventromedial Prefrontal Cortex and amygdala, which control emotional reactions and judgment.

The results demonstrated that mice without MAO-A were more aggressive, especially under stress. This implies that MAO-A influences the parts of the brain that regulate emotional reactivity, which is a key function in regulating aggressiveness.

The association between MAO-A and aggressiveness is supported by other studies, which highlights the part played by the gene-environment interaction. Increased aggressiveness has been linked to low-activity MAO-A gene variations, particularly when paired with environmental stresses or childhood trauma.

This connection implies that environmental variables can initiate or intensify aggressive tendencies, even while hereditary factors may incline people to them, as discussed by. These results highlight the need of considering both life events and genetic predispositions when analyzing aggressive behavior.

Using animal models, the brain processes by which MAO-A influences aggressiveness have been thoroughly investigated. When stressed, mice without functioning or low-level expression of MAO-A showed increased aggressiveness, according to research from Jackson Laboratory.

The vmPFC, which regulates impulsive behavior, saw decreased activity, while the amygdala, which processes fear and anger, became overactive. These findings imply that MAO-A affects aggressiveness by altering parts of the brain that control behavior and emotional reactions.

Furthermore, the function of MAO-A goes beyond aggressiveness, especially in conditions like Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder. According to a pilot research, OCD patients who had hypomethylation, which can lead to the activation of normally inactive genes, of the MAO-A gene promoter responded better to cognitive-behavioral treatment.

This implies that differences in MAO-A might affect how OCD develops as well as how well therapies work. This link highlights MAO-A’s wider significance in mental health and raises the possibility that treating a variety of impulsive and compulsive diseases may benefit from targeting this gene.

Future studies will likely keep looking into how behavioral differences in MAO-A interplay with other genetic and environmental variables. The impact of MAO-A activity in the brain on human aggressiveness and decision-making may be better understood thanks to developments in neuroimaging techniques like positron emission tomography.PET is a medical imaging technique that uses radioactive tracers to visualize and measure processes in the body, particularly in the brain. To better control impulsivity and aggressiveness, research might potentially concentrate on creating treatments that target MAO-A activity.

Ultimately, the MAO-A gene is essential for comprehending impulsivity and violence. Environmental effects, such as stress in early life, are just as crucial in forming violent behavior as hereditary elements.

To improve outcomes for people with aggression-related diseases and lessen aggressiveness, ongoing studies are continuously examining the interaction between hereditary and environmental variables.