William Bobrowski stands outside The Strand’s flagship store on Broadway, next to a table stocked with hot Dunkin’ coffee and sweets—a recharge station for strikers. He watches the bookstore’s workers chant, “don’t cross the picket line!”

After spending 22 years as a shop steward, he was disgruntled when the pandemic laid off over 40% of his colleagues. In June, he quit The Strand to devote all his time to the union UAW Local 2179. Today, he is the second vice president of Local 2179, represents his fellow booksellers and upholds the union’s legacy, which dates back to the 1970s.

Despite the cold on the first picketing day on Dec. 7, Bobrowski stayed to show his support.

“I’m their union representative,” he said, shivering in his trench coat, his gray-and-reddish beard framing his weathered face. “I was a shop steward for twenty something years—I’ll never let go of this place.”

A week later, The Strand workers ratified a new contract. The agreement includes a 37% raise, improvements to their healthcare plan, no reduction in personal days and a commitment from the company to hire above the minimum wage.

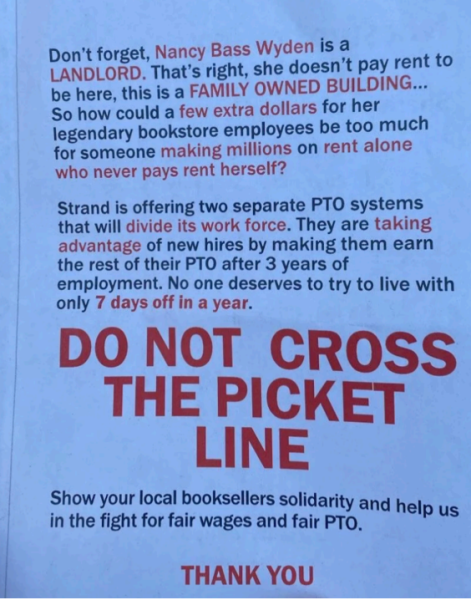

The Strand’s workers went on strike, brought by efforts to negotiate their union’s contract after it expired on Sept. 1. Prior to the new contract agreement, The Strand introduced two separate proposals to its workers. One required new hires to work three years before earning the same paid time off as current workers, which amounts to nine days. Additionally, The Strand offered a 50- cent annual raise while asking employees to pay 26% more for their insurance. Local 2179 is pushing for a $1.50 raise after the first year, $1.00 after the second and another $1.00 after the third.

With the minimum wage in New York City expected to rise to $16.50 in January 2025, the average bookseller at The Strand would earn $19.50 by 2028, per the new contract.

“Solidarity isn’t a bullshit word with us,” Bobrowski said. “We care and love each other too much and fight damn hard for every single member—even the ones who aren’t here yet.”

Across the street from Bobrowski, 27-year-old Brian Bermeo is at the bargaining table, a bookseller making 30 cents above the minimum wage. He said the company has stalled negotiations and argued it couldn’t find more money to pay workers. When asked point-blank, The Strand refused to say it couldn’t afford it—only that it didn’t want to give more.

“The store is raking in millions of dollars a year on weekends like this during the holiday season,” Bermeo said.

Bermeo noted that 92% of workers voted in favor of strike action. This led to the approval of a UAW strike assistance fund, providing workers with $500 a week, prorated over a seven-day period. Even probationary employees—as long as they have paid their initiation fees—are eligible for strike pay.

Many employees point to Nancy Bass Wyden, the owner and heir to The Strand, as a key figure in the bookstore’s labor challenges. Cyrus Keege, who has worked at the bookstore for 20 years, describes it as a laid-back used bookstore known for its low prices and vast selection. But over time, Keege says Bass Wyden shifted the store’s focus to new books and merchandise— like its infamous tote bag—raised prices and showed little regard for the union.

According to Bobrowski, Keege and Bermeo, Bass Wyden has not attended a single negotiation meeting. Bass Wyden did not respond to The Ticker’s requests for comment on the protest, but Carson Moss, The Strand’s chief operating officer, replied in an email.

“The union has not been willing to accept those increases so far,” Moss said in the statement. “We will continue to bargain in good faith and target a compromise that creates a bright future for the company, our employees, and customers.”

Despite the challenges, The Strand’s workers remain deeply committed to the store and its iconic name. Maria, 30, a bookseller who didn’t want to disclose her full name, described working at The Strand as a source of pride. She said the bookstore has a legacy, with authors like Luc Sante and Patti Smith, who once walked the aisles as booksellers.

Maria recalled her coworkers reading nonfiction books in the basement to help serve customers interested in business or science. She also remembers a summer when her manager fainted from heat exhaustion after higher-ups refused to turn on the air conditioner, but he still pushed through while taking out the carts in the morning.

When asked about a former employee’s tweet about a roach infested breakroom and a rotting rat in a heat pipe, Maria nodded and smiled. “Oh yeah,” she said. “That’s actually the least of our worries.”