The placenta, an organ that forms during pregnancy, is a key organ in a fetus’s development. It provides nutrients and antibodies to a developing fetus.

After birth, the placenta typically has no further use, however scientists have recently discovered that the placental tissue can be used in surgeries and to heal burns and wounds.

One such example of successful implementation of placental tissue is Marcella Townsend. Townsend survived a propane explosion at her mother’s house in Savannah, Georgia in 2021, which left her in a coma for six weeks.

She suffered second- and third-degree burns over most of her body and her face had become unrecognizable.

In an attempt to help her, surgeons turned to human placental tissue. A thin layer of the donated placenta was carefully applied to Townsend’s face.

“It was the best thing they could have done,” Townsend told The New York Times. Her face “looks exactly like it did before,” she said.

Another example is Sidney Akler. Akler suffered from a leg infection caused by damage to the blood vessels and was admitted to the ICU at Mount Sinai.

Akler was told his prognosis was bleak and his leg may have to be amputated. However, Akler was offered an alternative treatment thanks to the use of placental tissue.

“After weekly treatments, the wound has gotten [a] lot smaller than it was two years ago,” Akler told Sinai Health. “There is no definite time on when it will be healed completely, but it is getting a lot better.”

The positive outcomes of Townsend’s facial burns and Akler’s leg infection shows the usefulness of placental tissue postpartum. According to The New York Times, research has found placenta-derived grafts can reduce pain and inflammation, heal burns, prevent the formation of scar tissue and adhesions around surgical sites and even restore vision.

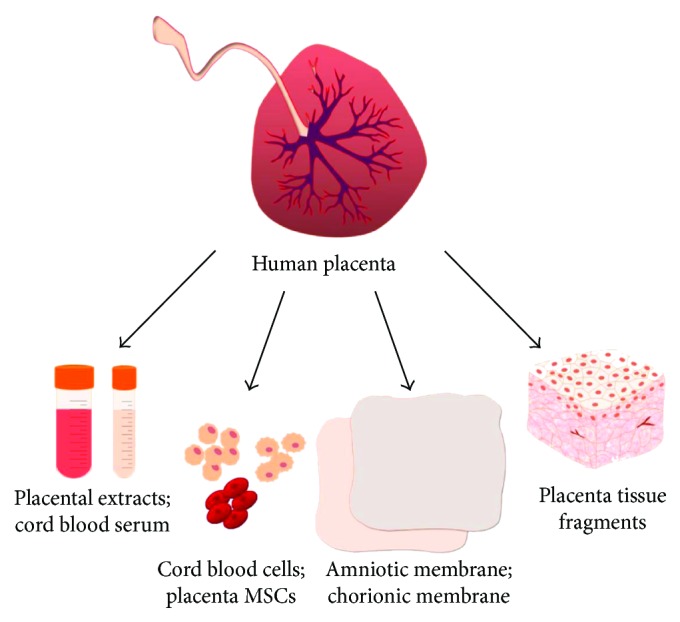

This could be because the placenta is still filled with a wealth of stem cells, collagen and cytokines even after birth.

According to The New York Times, despite its usefulness, of the roughly 3.5 million placentas delivered in the United States each year, most still wind up in biohazard disposal bags or hospital incinerators.

Townsend, who was able to return to her job as a surgical assistant, commented, “I’m constantly in these hospitals that don’t donate or utilize the placental tissue. I hear the obstetrician say, ‘I don’t need to send that to pathology or anything; just trash it.’ I cringe every time.”

While the use of placental tissue shows promise and was successful in both Townsend’s facial burns and Akler’s leg infection, it’s still a rare treatment.

To make placental grafts, manufacturers collect free placentas from prescreened donors. The amniotic membrane, the innermost layer of the placenta that faces the fetus, is peeled off and sterilized in a rapid process.

After it’s cut to a uniform size and shape and detailed quality checks are performed, the tissue is deep frozen, dehydrated or freeze-dried.

To use it on a patient, doctors unwrap a packaged slice of membrane and lay it over a wound or incision. The graft can be held in place with sutures or, in some cases, just a dressing.

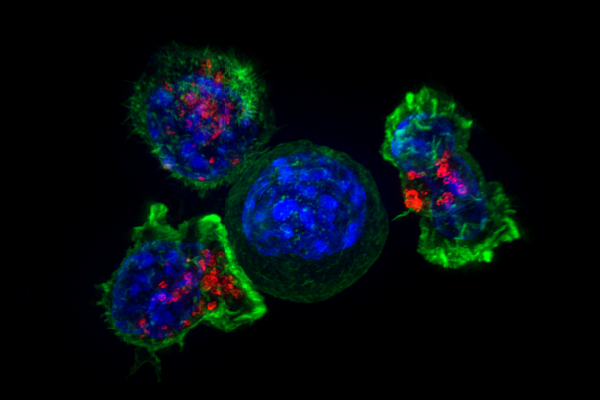

Because the placenta protects the fetus from the maternal immune system, its tissue is considered immunologically privileged.

Even though it is technically foreign tissue, placental grafts have been found not to prompt an immune response in transplant recipients. The use of placental tissue shows promise in surgical treatments.