New York Public Library brings J.D. Salinger into the 21st century

Courtesy of New York Public LibraryJ.D. Salinger’s most popular novel, The Catcher in the Rye, has sold over 65 million copies since it was first published in 1951.

November 18, 2019

Last month, the New York Public Library opened the J.D. Salinger exhibit and, in turn, revealed a new perspective into the life of one of the most enigmatic authors of the 20th century.

The exhibit, which will be open until Jan. 18, contains letters, photographs and other personal items on display that were all donated to the library by the J.D. Salinger Literary Trust.

The decision to donate hundreds of never-before-seen items was made by Salinger’s widow, Colleen Salinger, and his only son, Matt Salinger.

Matt Salinger admitted in an interview with Penguin Random House that he “thought it was time that the readers that [his] father cared most about should know some truths.”

The exhibit comes months after what would have been J.D. Salinger’s 100th birthday, born within blocks of Central Park and raised on 82nd street in the Upper West Side.

The most prominent detail upon entering the exhibit is Salinger’s vintage royal typewriter, the same one he used to write his most critically acclaimed work of prose, The Catcher in the Rye.

This coming-of-age story, focused on the angsty main protagonist Holden Caulfield, has become a seminal release in the history of American literature since its publication in 1951 and still resonates with readers of all ages to this day.

Original transcripts and drafts of Salinger’s short stories could also be found throughout the exhibit alongside copies of The Catcher and the Rye and his most popular novels — Franny and Zooey, Nine Stories and Raise High the Roof Beam, Carpenters and Seymour: An Introduction — translated into various languages.

Despite having an astounding influence on readers around the world and the counterculture of the 1960s in America, Salinger was committed to living a quiet life away from the spotlight.

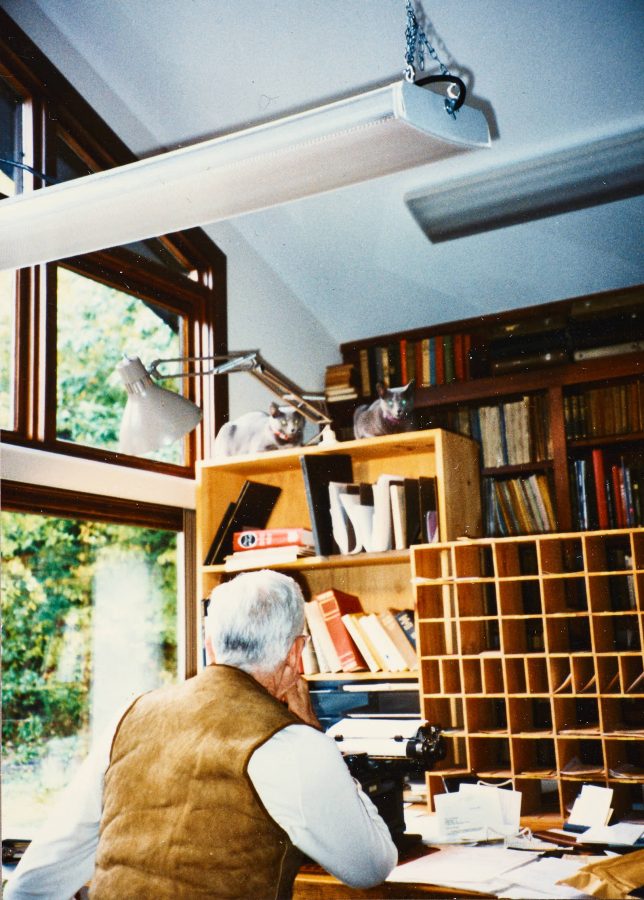

Often given the label of a hermit, Salinger moved from his apartment on East 57th Street in Manhattan to a farm in Cornish, New Hampshire only a couple of years after the publication of The Catcher in the Rye, and spent the rest of his life secluded from the media.

Salinger’s tendency to stray away from attention manifested in his writing in several forms.

He was highly involved in the decision-making for the cover art of his novels and often favored plain artwork.

On display at the exhibit is one of the first drafts of cover art for The Catcher in the Rye.

Salinger favored that draft because of its simplicity.

The author was also against the inclusion of his portrait on the inside of the book jacket and wanted no visual depictions of the main protagonist, Holden, included on the cover.

Subsequent to the film adaptation of one of his short stories — “Uncle Wiggily in Connecticut” — Salinger vehemently opposed any future transitions of his work to the big screen.

In the aforementioned interview with Penguin, Matt Salinger recalls that his father once wrote, “I write for the private screening room in each reader’s head: that’s the only movie screen I care about.”

Despite his shyness, there was nothing Salinger loved to do more than write, his son says, and the exhibit proves this.

Salinger’s keyring of notecards, which he always kept on himself to recall characters, dialogue, scenes and real-life incidents, is another one of his personal items on display.

Although his love for writing was immeasurable, Salinger published his last work in the 1960s and spent the rest of his life in solitude.

Matt Salinger tells Penguin that he is often asked if his father stopped writing entirely, to which he responds, “How can a writer stop writing?”

Matt Salinger also mentions his plans to release several of his father’s stories from the 1970s and 1980s in the next few years.

The exhibit is an amazing opportunity to get a deeper look into the life of an author who has left a mark on generations of readers and American literature as a whole, but stayed an enigma himself.