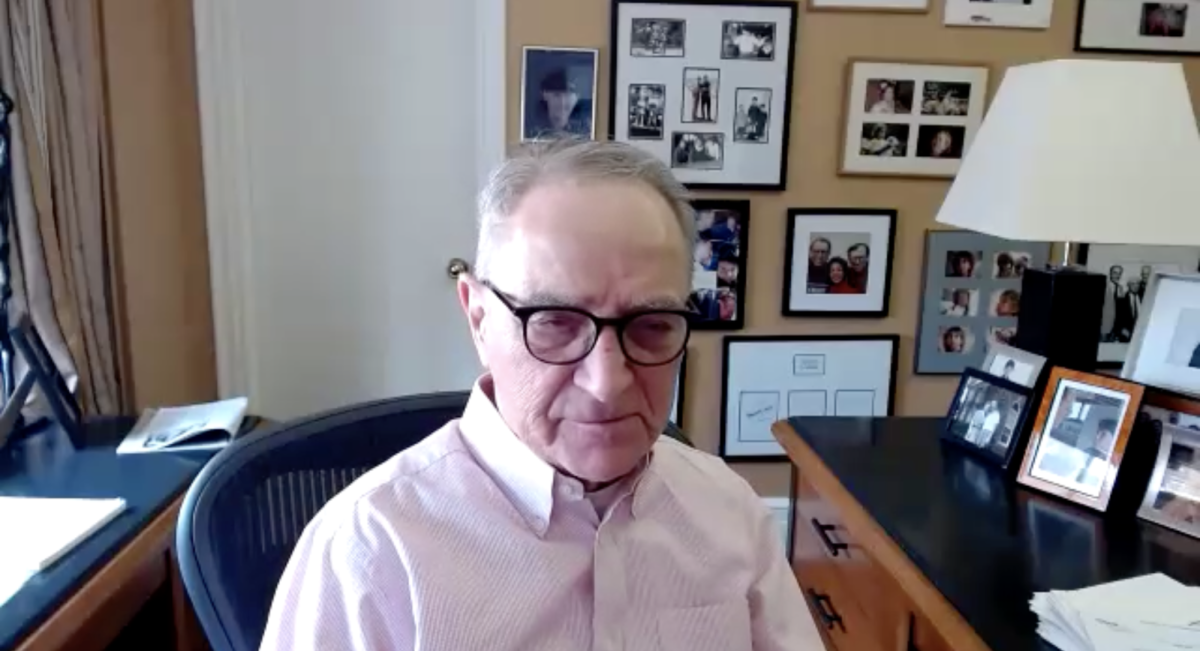

Zicklin School of Business namesake Larry Zicklin tackles the question of whether the insurance industry could help solve the climate challenge in the latest installment of his webinar series on April 9.

Zicklin started the webinar by asking if there is doubt in the insurance industry that climate change is occurring. Alice Hill — the David M. Rubenstein senior fellow for energy and the environment at the Council of Foreign Relations — expressed that insurance companies have stated climate change is a growing concern because of the impacts it could have on “the availability of insurance and economic growth.”

Lin Peng — Krell Chair Professor of the Department of Economics and Finance in the Zicklin School of Business at Baruch College — added that a recent article showed global insurance companies lost over $100 billion due to natural catastrophes, with a warning that the number could double within 10 years.

Zicklin asked if there were any solutions to mitigating the amount of fossil fuels used, to which both speakers said options include transitioning to renewable sources by pulling or burying carbon dioxide out of the atmosphere.

Hill added that the United States’ disaster response and recovery is under a system of moral hazard, where elected officials permit developers to build in areas with a high risk of climate catastrophes. She explained that this leads to “climate bailouts” where the government funds the rebuilding of these areas and assumes the risk.

Zicklin acknowledged that insurance companies are “profit-making institutions” and will continue to work in high-risk areas until there is no return on investment and the government bails them out, creating a “self-defeating proposition.”

Peng said short-term profits and the lack of technologically advanced tools used to assess climate risk are what causes insurance companies not to make “prudent decisions.”

When asked who is developing the new climate tools and whether they are shared with corporations and the government, the speakers noted that the private sector creates the tools, and they are not a “public good” yet.

Additionally, the speakers expressed that having access to advanced climate tools could help investors make their portfolios safer by assessing “related risk in financial assets.”

Zicklin responded by asking if insurance companies would be forced to disclose their modeling techniques. Peng said that evaluating environmental and climate-related risks is complex because there is no consensus on evaluating and predicting environmental ratings.

Before transitioning to a moderated Q&A session, Zicklin asked what industries are prone to climate change’s effects. The speakers answered: agriculture, finance, manufacturing and fossil fuel utilities.

During the Q&A session, the speakers were asked how companies could incorporate climate risk into their risk management strategies. Hill stated that companies need “an expert” and it needs to be a board-level issue, while Peng said companies need to consider the transition risk.

“For example, regulation may be coming; you have to shift away from carbon-intensive technology and transit[ion] to renewable technology or your competitors may have cheaper ways to using renewables to produce energy, and you have to compete with that and there could be changes in consumers preferences,” Peng said. “So, there are a lot of considerations beyond the physical risk, but in the kind of the transition risk domain that a company will have to take into consideration.”

To close the webinar, an attendee asked Peng if she could elaborate on her students — Peng teaches IDC4010 — and what takeaways they get from her course. Peng answered by saying the students were already conscious of climate issues, and the main takeaways are that there are lots of scenarios that could be a win-win for corporations and the environment.

“The world is not black and white, and there are a lot of places where we can strive for win-win solutions where we can benefit the shareholders, but also the community at large,” Peng told the audience.