Baruch College assistant chemistry professor Baofu Qiao joined researchers at Northwestern University in developing a new selective therapy that prevents allergic reactions.

The groundbreaking study is the first to successfully prevent anaphylaxis, a severe immune system response that can lead to itchy hives, troubled breathing and death.

Qiao supervised the study’s atomistic simulation, which modeled nanoparticles to see how they interact.

“All the proteins and polymers are interacting with each other and [the] molecules,” Qiao said in an interview with The Ticker. “Because all kinds of molecules are interacting with each other by means of atomic interactions. So, if we can understand the atomic interactions, how they are reacting with each other, and we can explain many kinds of microscopic observations.”

Previously, there have been no methods to prevent anaphylaxis besides avoiding allergens.

“The biggest unmet need is in anaphylaxis, which can be life-threatening,” study co-author and allergy expert Bruce Bochner said. “Certain forms of oral immunotherapy might be helpful in some cases, but we currently don’t have any FDA-approved treatment options that consistently prevent such reactions other than avoiding the offending food or agent. Otherwise, treatments like epinephrine are given to treat severe reactions — not prevent them.”

The pilot mouse study was published in the Nature Nanotechnology journal on Jan. 16 and exhibited a 100% success rate in averting allergic responses without noticeable side effects.

“Mouse mast cells do not have Siglec-6 on their surface like in humans, but we got as close as we could for now to actual human studies by testing these nanoparticles in special mice that had human mast cells in their tissues,” Bochner said. “We were able to show that these humanized mice were protected from anaphylaxis.”

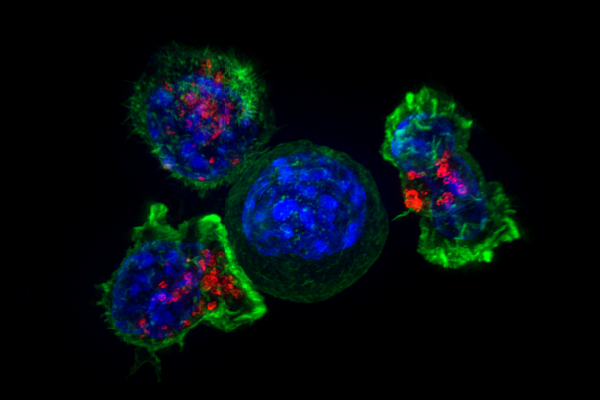

The therapy follows a two-step process where the allergen engages specific mast cells responsible for the allergy and the antibodies shut them down. This method allows the treatment to prevent specific allergies without weakening the immune system.

“You can use any allergen that you want, and you will selectively shut down the response to that allergen,” Northwestern lead researcher Evan Scott said. “The allergen would normally activate the mast cell. But at the same time the allergen binds, the antibody on the nanoparticle also engages the inhibitory Siglec-6 receptor. Given these two contradictory signals, the mast cell decides that it shouldn’t activate and should leave that allergen alone.”

Qiao said he was surprised to find that the nanoparticle’s surface is adaptive and adjusts its polar and nonpolar domains based on nearby antibodies. The nanoparticles contain a soft surface that preserves the antibodies’ function while targeting proteins.

The study’s results have a vast implication for treating mast cell diseases.

Researchers plan to examine the nanotherapy’s effectiveness on other diseases like mastocytosis – a rare form of mast cell cancer. They are also exploring methods to fill the nanoparticles with drugs to selectively eliminate excess mastocytosis cells without harming other cell types.

“At this moment, we still have very limited understanding [on] why these molecules are the right models,” Qiao said. “We still have a lot to learn about these molecules.”