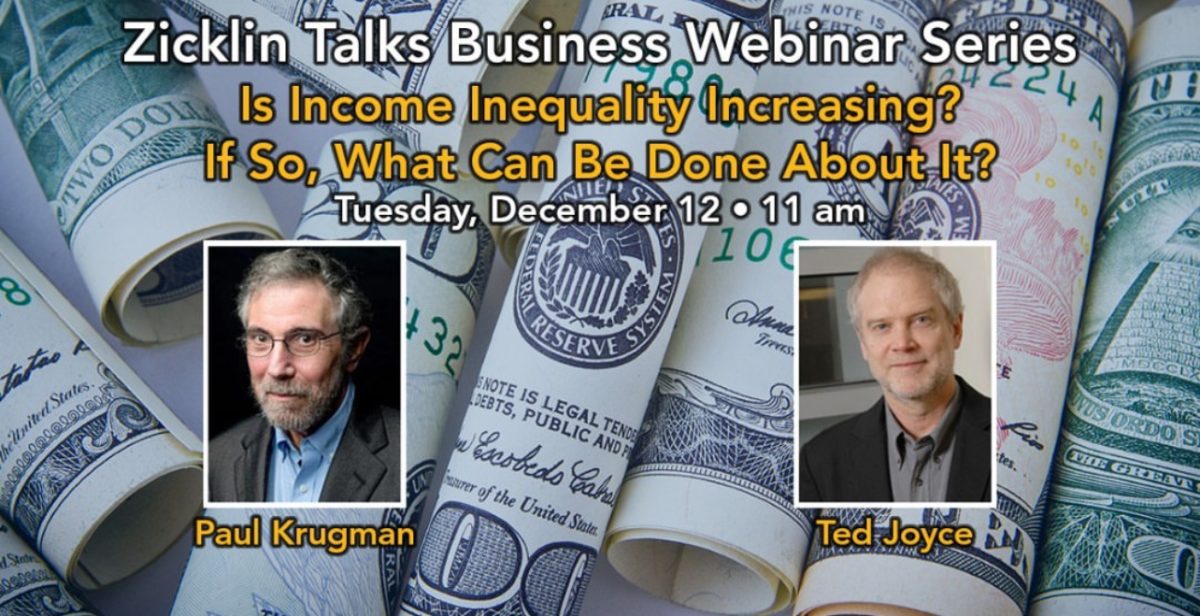

Income inequality, its definition and its implications for businesses and consumers were the focus during a conversation between Baruch College alumnus Larry Zicklin and economist Paul Krugman in a webinar on Dec. 12, 2023.

Krugman, who is a Distinguished Professor of Economics at the CUNY Graduate Center, joined the namesake of Baruch’s business school for the last installment of the “Zicklin Talks Business” webinar series for 2023. The professor is also known as the winner of the 2008 Sveriges Riksbank Prize in Economics Sciences.

When asked if there is an accepted definition for “income inequality,” Krugman said there are several definitions, all of which he uses.

But the economist said he uses the 90-to-10 ratio — comparing the wages and salaries of workers in the 90th percentile to wages and salaries of workers in the 10th percentile — frequently. He noted that regardless of the type of definition, each one tells “the same story” of the history of income inequality in the United States.

“I’ll use any and they all tell the same story, which is that American society got a lot more unequal,” Krugman said. “It got a lot less unequal in the sort of 1940s and then became a lot more unequal starting around 1980 and continuing at least until fairly recently.”

When asked by Zicklin if there is a universal agreement on his trajectory of income inequality, Krugman said a “handful of economists” would debate it, but the numbers are unambiguous.

He told attendees that if current U.S. society does not look more unequal now than in 1973, then they “must not have been paying attention back then.”

Krugman posed the idea that technological changes that heighten demand for highly skilled workers have led to increased income inequality. He said that the change in norms and loss of the “checks and balances” on high inequality played a bigger role.

In the 1960s, corporate CEOs were paid 30 times as much as the average employee compared to now, which is around 300 times, Krugman added.

“The weakening of the union movement and changes in norms played a big role,” he said. “We know that unions were a quarter of the workforce into the seventies and are barely existent in the private sector now.”

During negotiations between the United Auto Workers union and the “Big Three” Detroit-based car manufacturers, comparisons between the compensations of CEOs and workers were used effectively in arguments, Zicklin said.

Krugman noted wage income inequality declined over recent years. But over a broader time horizon, it has grown significantly, leading him to ask — “is inequality increasing?”

“I was wondering a little bit on what the meaning of the word ‘is’ is,” he said. “Inequality has clearly increased enormously over the past forty years. It may have gone down in the past three years.”

Low unemployment is important in decreasing income inequality, Krugman said, adding that people have imagined that the economy could return to normal inflation levels with an unemployment rate of 3.7%.

Yearly data is stale and looking at semi-annual data is a more accurate representation of the economy, he added.

The facts of the data differ from people’s feelings toward the economy, said Ted Joyce, an economics professor in the Bert W. Wasserman Department of Economics and Finance, said.

Krugman cited people having a longer time horizon as the reason, while Zicklin said that it does not matter what the facts are. People can talk the economy down if they are “inventive enough on social media,” the Baruch alumnus said.

Wealth inequality also follows a similar story to income inequality, Krugman said.

But he said wealth is “enormously more unequal than income” because most people’s only financial asset is their home — assuming they own it — speak with higher-income people who possess more financial assets, creating a cushion for them against “year-to-year fluctuations.”

Following the discussion, the webinar transitioned to an open Q&A.

When asked how business schools can better facilitate social mobility for all the students — especially at Baruch — Zicklin School dean Bruce Weber said that these schools give disadvantaged students access to classroom learning and tacit knowledge, so he actively looks for opportunities outside of the classroom, like developing students’ “professional life skills.”

Krugman added that emphasizing that providing an affordable and rewarding education for disadvantaged students is the “CUNY difference.”

Zicklin said that business schools can “be very sensitive to where the opportunities are in business and make sure they’re preparing students with that in mind,” so they “have to be on the cutting edge of what’s going on in business society.”

“We have to be aware of what’s being required of graduates,” he added. “We have to provide that education for them.”