The United Auto Workers union struck tentative deals with all three of the Detroit Three automakers, signaling the culmination of the six-week strike on Oct. 30.

General Motors negotiated a deal that was fully fleshed out by Nov. 4 that mirrored the terms of the tentative agreement with Ford after the UAW expanded its strike to hit another one of GM’s major factories in Spring Hill, Tennessee, increasing pressure on the automaker to sign a contract.

As part of the agreements with Ford and Stellantis, workers are expected to receive an approximately 33% wage increase, including a cost-of-living adjustment, over the course of the nearly five-year contract. Further details included significant pay increases for temporary workers and a shortening of the time necessary for workers to reach the highest pay rate.

Notably, Stellantis’ deal includes commitments to expand production and prevent plant closures, which the union said would create 5,000 unionized jobs.

“Through the grapevine, I hear it’s pretty good and that’s really a blessing for all of us, all the UAW workers,” DeSean McKinley, a worker at Stellantis’ Sterling Heights assembly plant in Detroit, said.

According to Ford and GM, the strikes have cost the respective companies $1.3 billion and $800 million in earnings. Stellantis did not comment on how the strike has impacted its bottom line. According to Ford’s chief financial officer, John Lawler, the company produced 80,000 fewer vehicles as a result of the strike. He added that the renegotiated contract would increase the cost of labor per vehicle by approximately $850 to $900, requiring the company to find efficiency in other areas.

With higher labor costs, the Detroit Three will have greater difficulty in remaining competitive in the face of their non-unionized rivals, such as Tesla and Toyota.

“The Detroit Three enter a new, dangerous era,” Professor Erik Gordon at the University of Michigan said. “They have to figure out how to transition to EVs and do it with a cost structure that puts them at a disadvantage with global competitors.”

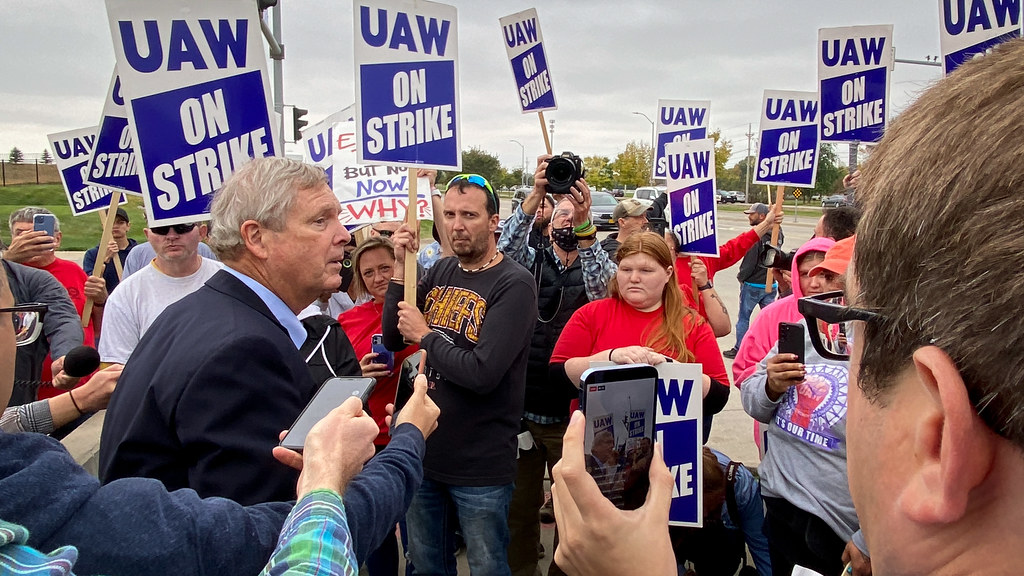

The end of the strike comes as a victory for the UAW and for the resurgent U.S. labor movement more broadly. Part of its success was due to UAW President Shawn Fain’s use of the unorthodox tactic of “stand up strikes,” targeting strikes at supply-chain critical factories rather than engaging in a general strike.

The shutdown of the critical factories forced automakers to lay off workers in non-striking factories. However, unlike striking workers, laid-off workers would then collect unemployment benefits rather than the UAW’s limited strike funds, thus allowing the union to continue the strike for longer than it otherwise would have.