A study conducted by scientists at the University of Rochester transferred genetic material from naked mole rats to mice, extending the lifespan of the mice.

Extending longevity has long been a major area of interest for scientific exploration. Naked mole rats are interesting animals to explore in this area as they have been recorded to live up to 41 years, nearly ten times longer than other rodents of similar size.

Compared to other species, naked mole rats also rarely contract diseases, including special resistance to neurodegeneration, cardiovascular issues, arthritis and cancer.

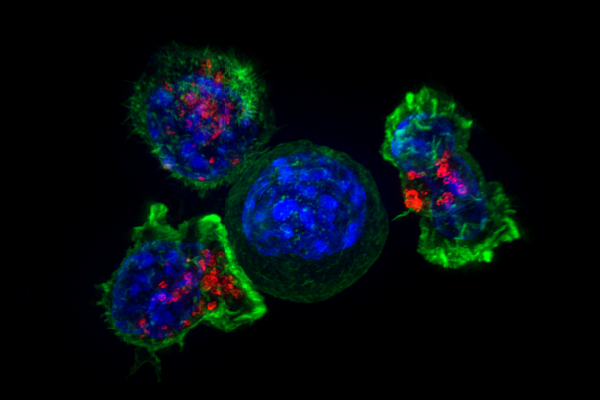

The researchers previously found this to be linked to the gene hyaluronan synthase 2 — responsible for the production of a protein, hyaluronan, that in turn produces high molecular weight hyaluronic acid, or HMW-HA. Though all mammals produce this molecule, it was found that naked mole rats had about ten times as much HMW-HA as mice and humans. When the gene responsible for HNW-HA production was removed from the naked mole rats, they were much more likely to develop tumors.

The researchers at University of Rochester modified mice to express the gene that produced ten times the amount of HMW-HA. As a result, the mice had improved health and had a median lifespan increase of 4.4%. Applying that change to the U.S. life expectancy of 76.4 years, that’s the equivalent of an extra 3.4 years in humans.

The mice also had healthier guts and less body-wide inflammation, a noticeable sign of aging.

“Our study provides a proof of principle that unique longevity mechanisms that evolved in long-lived mammalian species can be exported to improve the lifespans of other mammals,” Vera Gorbunova . “She and Andrei Seluanov are both professors of biology and medicine at the University of Rochester whose unit was responsible for the discovery.

“These findings demonstrate that the longevity mechanism that evolved in the naked mole-rat can be exported to other species, and open new paths for using HMM-HA to improve lifespan and healthspan,” according to the Nature research article.

This also opened the door to more research to be conducted on the topic of HMW-HA and its ability to be clinically relevant in humans.

Extending this benefit to humans seems relatively easy in theory. One way would be to slow down hyaluronan degeneration; the other would be to ramp up its production. The researchers at the University of Rochester currently have their sights set on the former.

“We already have identified molecules that slow down hyaluronan degradation and are testing them in pre-clinical trials,” Seluanov . “We hope that our findings will provide the first, but not the last, example of how longevity adaptations from a long-lived species can be adapted to benefit human longevity and health.”